Month: December 2015

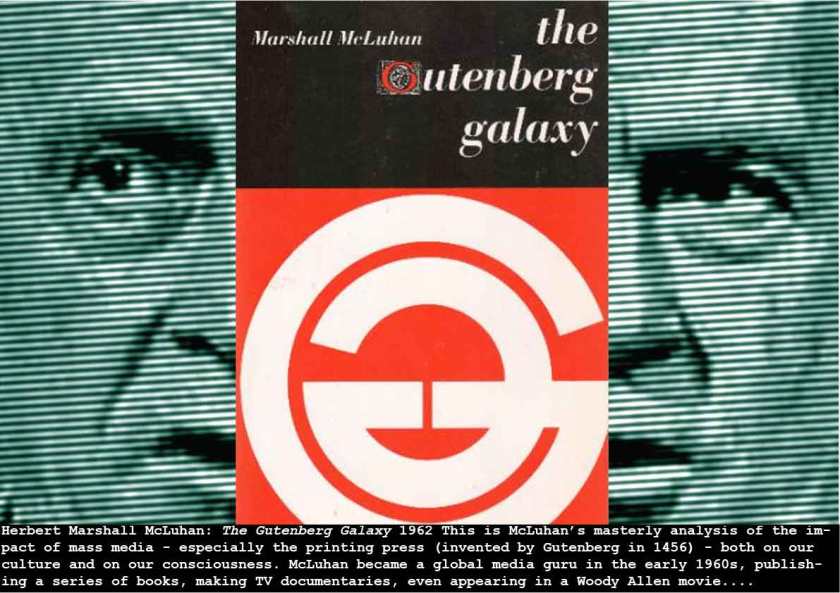

Herbert Marshall McLuhan 1962

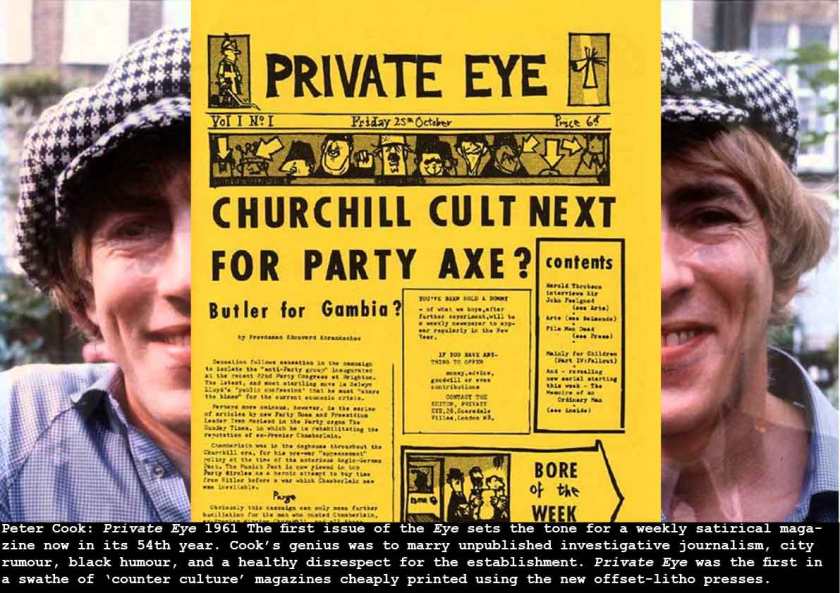

Peter Cook 1961

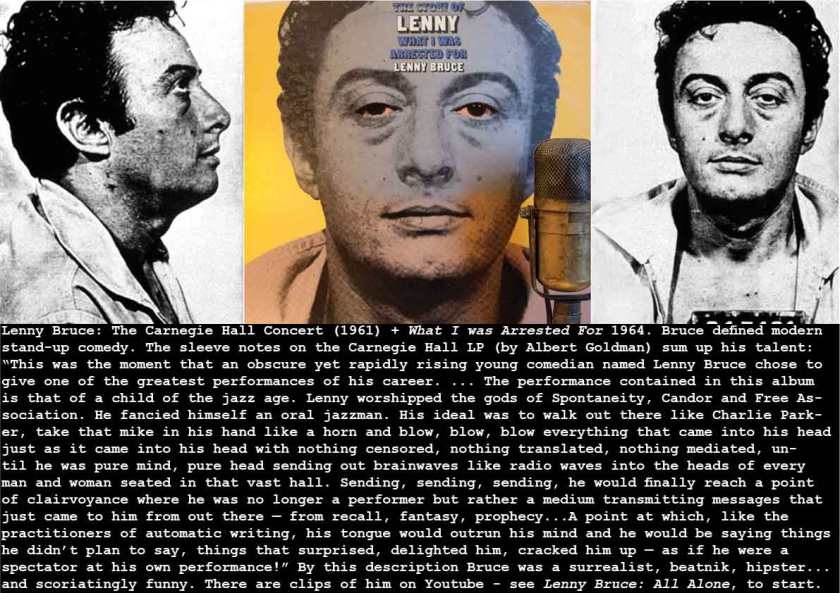

Lenny Bruce 1961

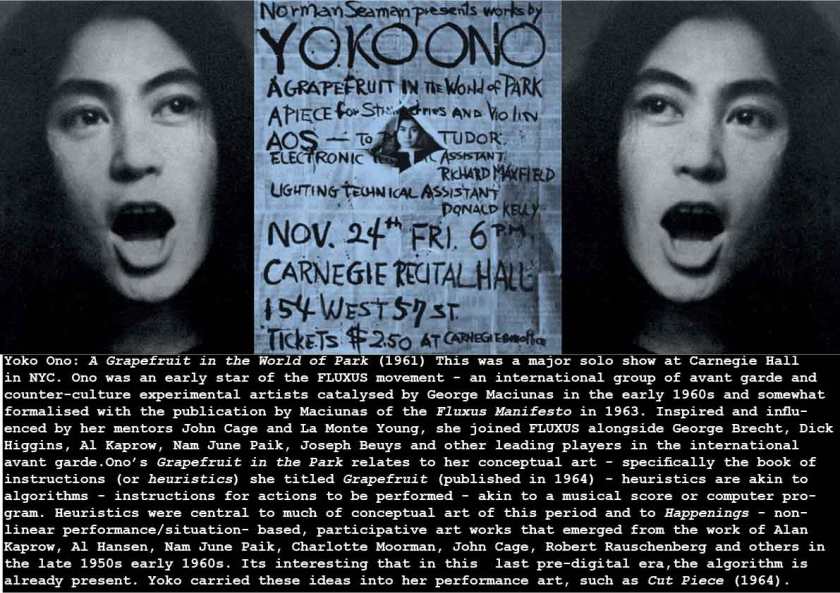

Yoko Ono 1961

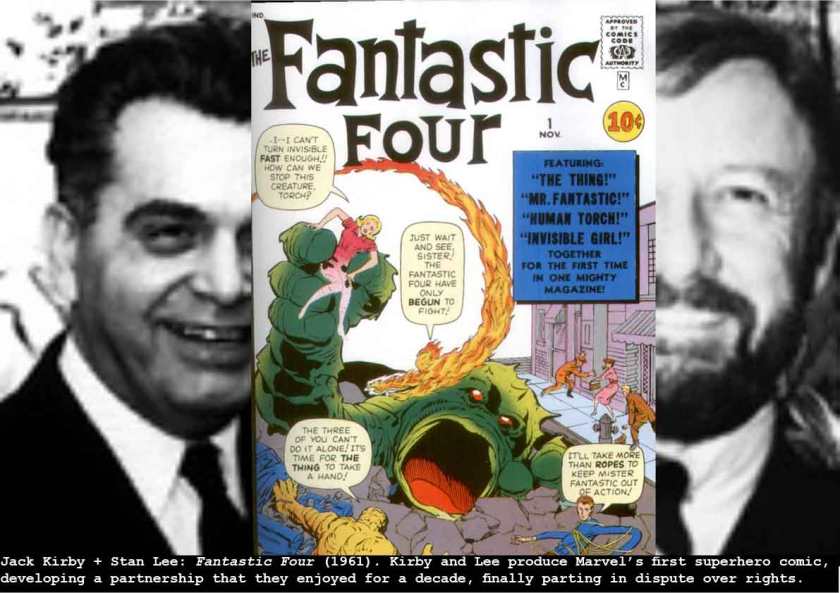

Jack Kirby + Stan Lee 1961

Above all others, Marvel Comics in their Sixties iterations, seemed to punctuate the extraordinary cultural developments in the West with entirely apposite and appropriate versions of old mythologies and their own brand of new myths. From Thor, Asgard and the Rainbow Bridge, to The Silver Surfer – that icon of the late Sixties – Stan Lee (working with a number of artists, but predominately with veteran Jack Kirby) repeatedly found the perfect combination of myth, fantasy and graphic style to generate a series of highly successful commercial products that transformed popular culture.

For instance, my favourite reading in the late Sixties and early Seventies included Marvel comics alongside Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds Science Fiction, Theo Crosby’s Architectural Design, New Scientist, OZ magazine, Rolling Stone, Peace News, and the International Times. But generally, the character development of Marvel – chiefly the work of Stan Lee, collaborating with artists like Jack Kirby, Jim Steranko, Steve Ditko (etc) – was brilliant – both in the sense or being very finely pitched to the developing tastes of Western youth, and in modern myth-making.

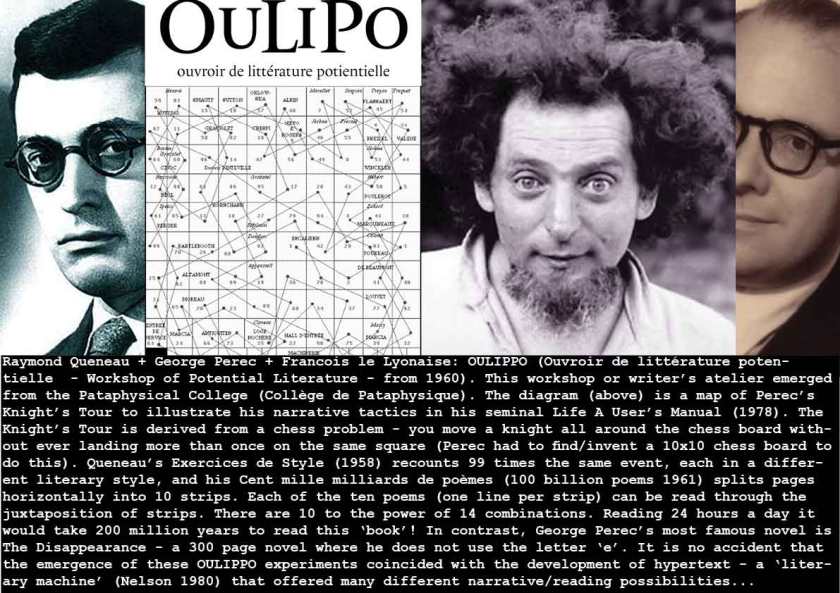

Queneau + Perec + le Lyonaise 1960

Right at the beginning of the Sixties, a group of avant garde writers, mathematicians and conceptual artists gather to explore the future of literature – and the ideas that will inform much of our cultural history. They form a workshop to explore Potential Literature – notions of chance, excision, linking, symmetry, algorithms, and “the seeking of new structures and patterns which may be used by writers in any way they enjoy.” In a decade that saw the coining of the word hypertext (Nelson 1965) and the programming of the first hypertext system (Van Dam 1968), OULIPPO’s adventurous exploration of literary form and composition lays the conceptual foundations.

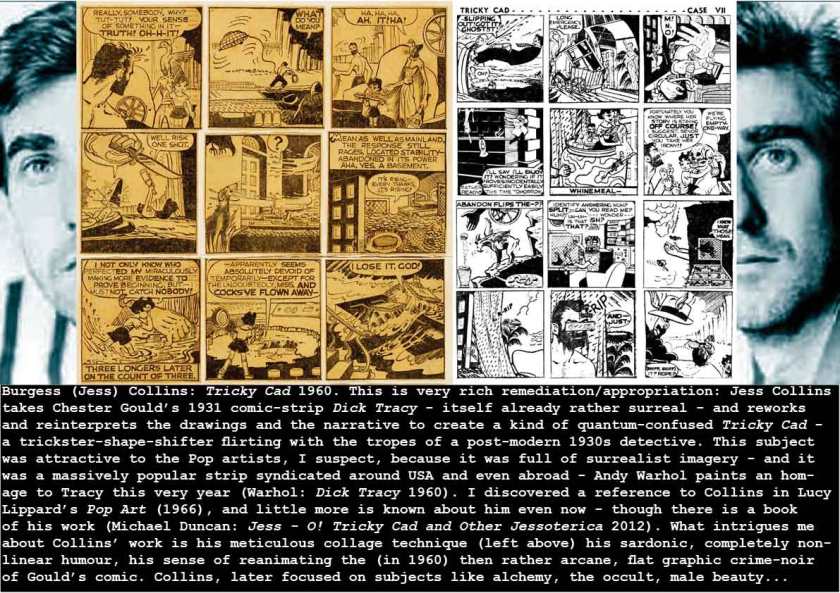

Burgess (Jess) Collins 1960

Although the seeds of Pop Art – ‘fine’-art based upon popular culture – had been sewn earlier in the century (Eduardo Paolozzi 1947, Richard Hamilton 1956), the flowering of pop art in America is really a Sixties phenomenon, and here in 1960 we have Jess Collins with his enormously entertaining deconstruction and remediation of Chester Gould’s comic strip from the 1930s. Gould’s Dick Tracy reformulated and reconstructed as Tricky Cad, creates a world conceptually even more surreal than the original (Gould was brilliant at inventing hyper-real villains). I love Gould’s graphic style – the flat, two-dimensional world that he creates with his unbreakable rectangular grid of frames, and I love too the way that Collins recasts these graphic devices into a series of existential excerpts. This body of work easily stands alongside that of the other great narrative collagist of the 20th century – Max Ernst (Les Malheurs des Imortelles 1922, Une Semaine de Bonte 1934, etc)

Joseph Licklider 1960

It’s very appropriate to begin the 1960s with a far-seeing paper by a scientific visionary, whose work defined much of the underpinning engineering of our 21st century cyber-culture. Man Computer Symbiosis! The title itself grapples with a recurring zeitgeist theme of the 20th century, first given expression in Raoul Hausmann’s iconic Spirit of Our Time in 1921. It was Licklider’s seminal paper that kick-started several major strands of research during his tenure at ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency) – the government-funded agency that oversaw the invention of the future in the USA. It was ARPA that invented the Internet (1969-1972), the idea of the personal computer (Engelbart 1968), computer graphics, 3d CG-modelling and simulation, and sowed the seeds of the graphical user interface (Engelbart 1968, Kay 1973). And it was Licklider’s vision – expressed in Man Computer Symbiosis (1960), the Intergalactic network idea (1962), Libraries of the Future (1965), The Computer as a Communications Device (1968), that drove this multi-million dollar investment in cyber-infrastructure.