J.C.R. Licklider: Man-Machine Symbiosis 1960

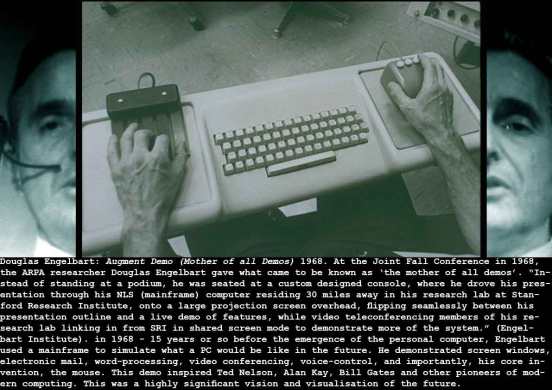

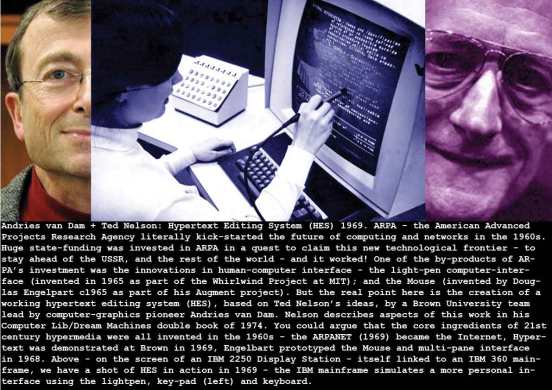

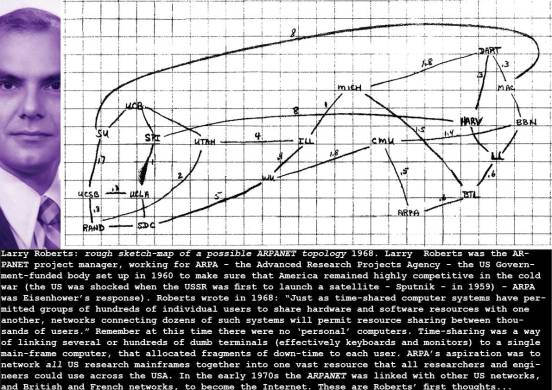

The Sixties are especially significant in the kind of art-media-cultural developments we are cataloging here in this timeline (or what Philip Jose Farmer called a ‘chronoscope’ and Buckminster Fuller a ‘chronofile’). Essentially because during the 1960s, we began to develop most of the technologies that underpin our 21st century media-space. And it was the American Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) that really kick-started the building of the basic infrastructure that we inherited. ARPA’s enlightened, State-funded research programmes spanned computer-science, networking, human-computer interface design, computer-graphics, modelling and simulation at the same time that aerospace and telecoms engineers were building the communications satellite infrastructure glimpsed as early as 1945-46 by Arthur C. Clarke and the scientist/engineers at RAND Institute. In the 1960s the US Military completed several versions of the SAGE early-warning air-defense networks, and by the late Sixties, ARPA had initiated a inter-computer network in the USA that resulted in the Internet in the early 1970s. By 1968 an ARPA-funded researcher, Douglas Engelbart, using a mainframe computer linked to a dumb-terminal demonstrated how a networked personal computer might work in the 1980s… (To illustrate the importance of ARPA, see Mariana Mazzucato‘s The Entrepreneurial State 201 – which argues that the US state-funded ARPA invented much of the core technology that underpinned the networked-multimedia revolution of the 1990/2000s – ie it was not private enterprise, but public enterprise, that built our modern mediated world.)

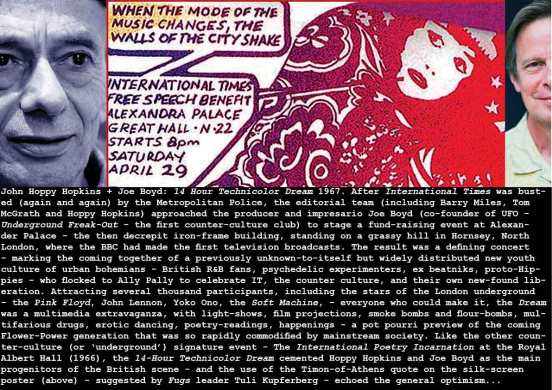

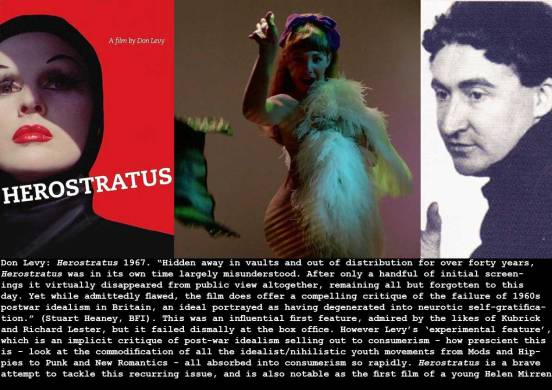

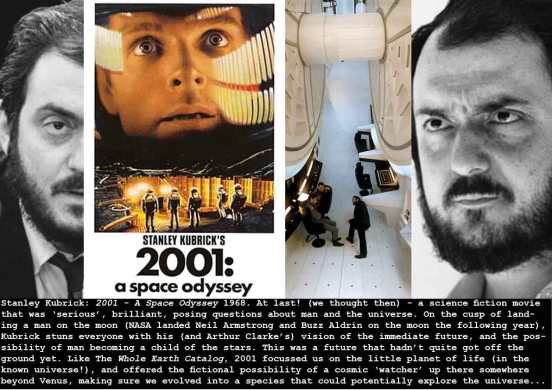

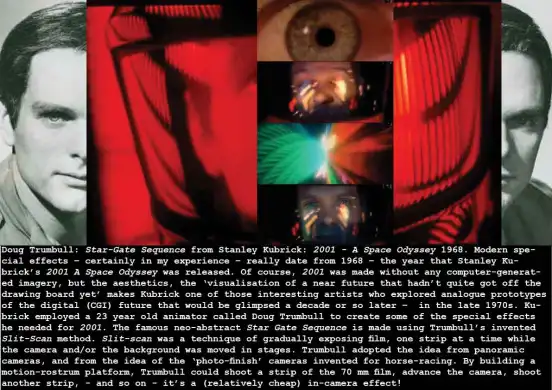

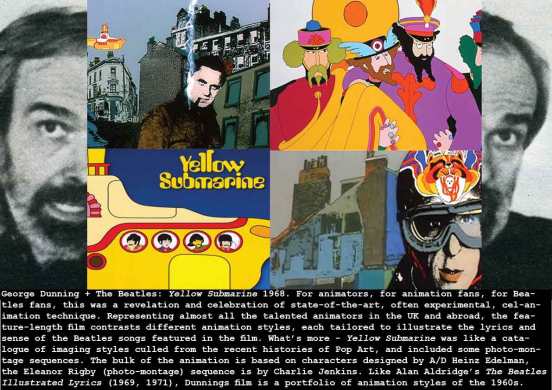

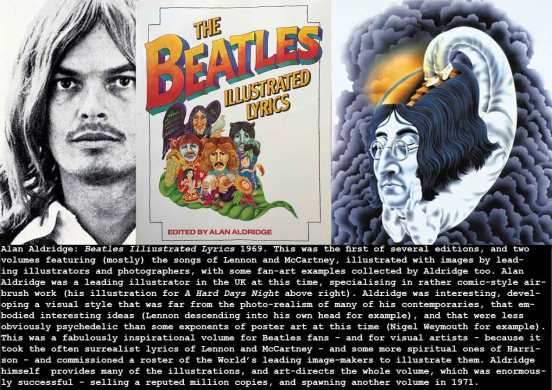

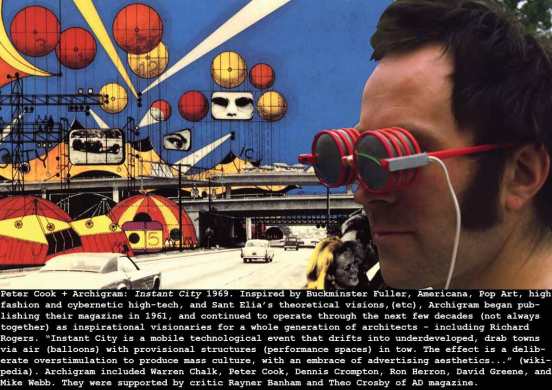

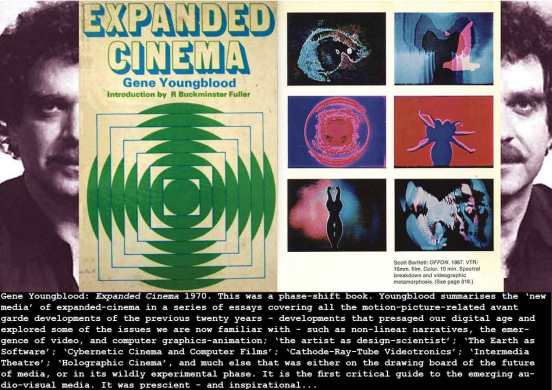

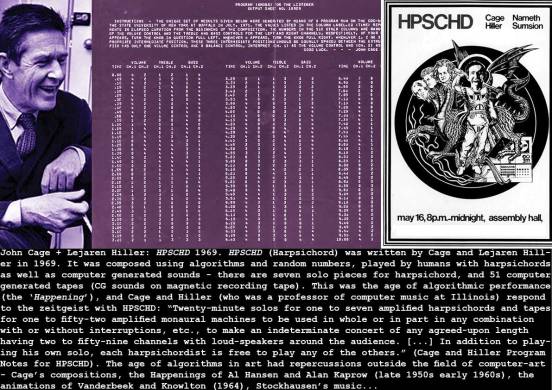

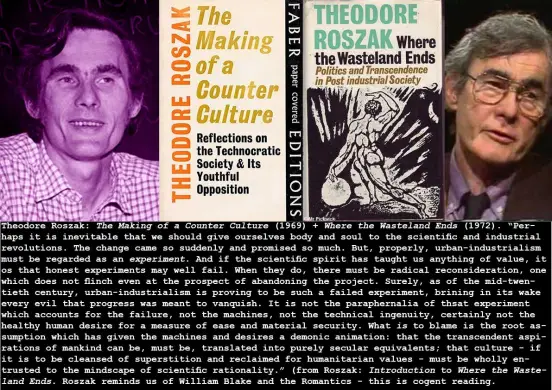

As early as 1961, the computer-pioneer Jay Wright Forrester had shown that complex systems – like factories and businesses – could be modelled in a computer, and simulations created to improve management strategies. By 1971, Forrester’s Systems Dynamics approach was applied to creating World Dynamics a computer-model of the entire World and its resources. And apart from these media-technology innovations, the decade established Britain as a vibrant source of cultural content-invention – in popular music, fashion, fine arts, design, and life-style, and even more radical – the 1960s was the decade during which the counter-culture and avant garde became a dominant influence. The Beatles Sgt Pepper and Beach Boys Surfs Up, Barbara Rubin‘s 1965 International Poetry Incarnation at the Albert Hall, the 1969 Woodstock and Isle of Wight Festivals established this – and the new Hollywood adventures of Dennis Hopper, Arthur Penn, Robert Altman, Stanley Kubrick, Doug Trumbull and others proved it at the box office. Echoing the rapidity of technical developments (cataloged in Gene Youngblood’s book Expanded Cinema in 1970), and the burgeoning cultural changes of the 1960s, the arts were evolving into a kind of celebration of mixed-media as we experienced concrete poetry, happenings (algorithmic theatre), auto-destructive art, pop-art, performance art, rock music, and the rest of the counter-culture impact (drugs/long hair/burning bras etc) on mass culture.

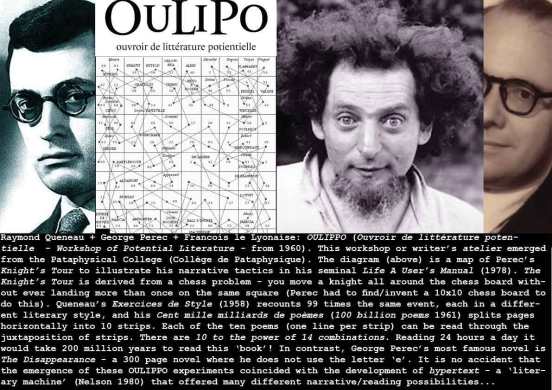

Raymond Queneau + George Perec + Francois le Lyonaise: OULIPPO (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle – Workshop of Potential Literature – from 1960)

Right at the beginning of the Sixties, a group of avant garde writers, mathematicians and conceptual artists gather to explore the future of literature – and the ideas that will inform much of our cultural history. They form a workshop to explore Potential Literature – notions of chance, excision, linking, symmetry, algorithms and “the seeking of new structures and patterns which may be used by writers in any way they enjoy.” In a decade that saw the coining of the word hypertext (Nelson 1965) and the programming of the first hypertext system (Van Dam 1968), and the flowering of Poesie Concret, OULIPPO’s adventurous exploration of literary form and composition lays the conceptual foundations.

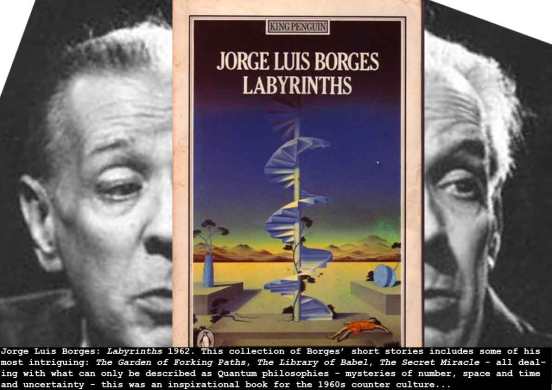

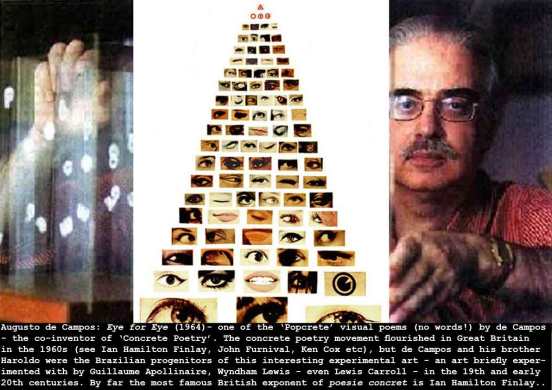

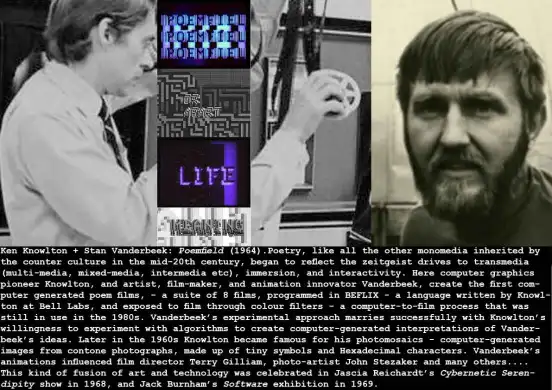

This is quite fascinating – within a few years we have OULIPPO, we have Borges’ stories about ‘impossible books’ and maze-like libraries (seed ideas for Umberto Eco); we have concrete poetry – poems as multi-dimensional texts (see Ian Hamilton Finlay, Augusto de Campos, John Furnival, Ken Cox etc), and we have the emergence of hypertext, with all of the possibilities of interactive narratives, Ted Nelson’s Xanadu vision of a universe of interlinked texts… The visions, the ideas, the technologies – of an ocean of inter-textuality, a garden of forking paths, books too long to ever read, books with missing letters, poetry algorithms (see Stan Vanderbeek + Stan Knowlton: Poemfield 1964):, poems materialised in stone and concrete; poems as typographic images; poems recited to jazz and to rock music; kinetically-powered poetry machines; appropriated, remediated texts; computer-composed poems …What was going on?

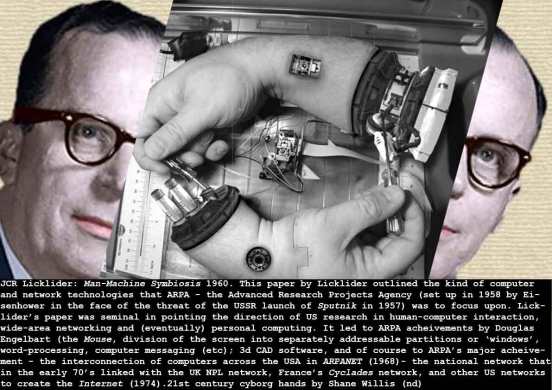

JCR Licklider: Man-Computer Symbiosis 1960

It’s very appropriate to begin the 1960s with a far-seeing paper by a scientific visionary, whose work defined much of the underpinning engineering of our 21st century cyber-culture. Man Computer Symbiosis! The title itself grapples with a recurring zeitgeist theme of the 20th century, first given expression in the man-machine symbiosis of Raoul Hausmann’s iconic Spirit of Our Time in 1921. It was Licklider’s seminal paper that kick-started several major strands of research during his tenure at ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency) – the government-funded agency that oversaw the invention of the future in the USA. It was ARPA that invented the Internet (1969-1972), the idea of the personal computer (Engelbart 1968), computer graphics, 3d CG-modelling and simulation (Sutherland 1963), and sowed the seeds of the graphical user interface (Engelbart 1968, Kay 1973). And it was Licklider’s vision – expressed in Man Computer Symbiosis (1960), the Intergalactic network idea (1962), Libraries of the Future (1965), The Computer as a Communications Device (1968), that drove this multi-million dollar investment in cyber-infrastructure.

Tom Lehrer: Masochism Tango c/w Poisoning Pigeons in the Park (45rpm single)1960

Tom Lehrer, Lord Buckley – Christopher Logue’s Red Bird EP – Howling Wolf’s Pye R&B label singles, Jules Feiffer’s sardonic cartoons, Saul Steinberg’s drawings, Albert Camus: L’Etranger, Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale, Jack Kerouac’s The Subterraneans – these were the cult media to my generation hitting 15 years old in 1960. The cult-status had been awarded by the generation born a decade or so earlier – the generation who invented Rock’n’Roll, the Beats, Jazz Festivals, blouson noirs, existentialist literature – and eagerly grasped at clues to the alternative lives we wanted to explore – lives not conditioned by 9-5 conformity, consumerism, short hair, Burton suits, boring jobs. Here was the acidly satirical emetic for all that, cleverly orchestrated in Lehrer’s parched-dry crazy-edged humour – the Masochism Tango!

his spoken intro: “Another familiar type of lovesong is the passionate or fiery variety, usually in tango tempo, in which the singer exhorts his partner to haunt him and taunt him and, if at all possible, to consume him with a kiss of fire. this particular illustration of this genre is called the Masochism Tango.”

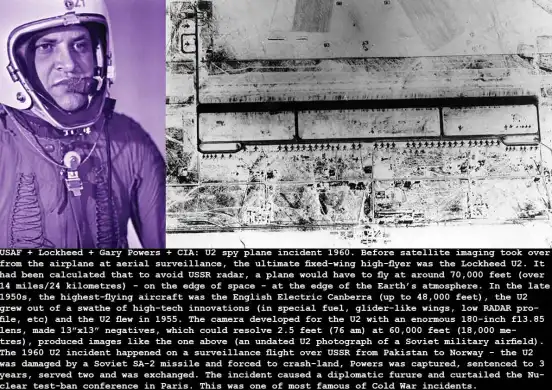

USAF + Lockheed + Gary Powers + CIA: U2 spy plane incident 1960

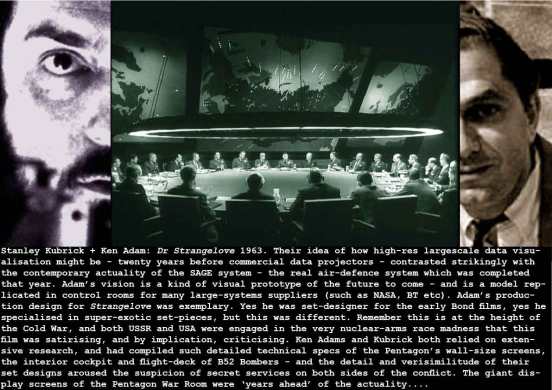

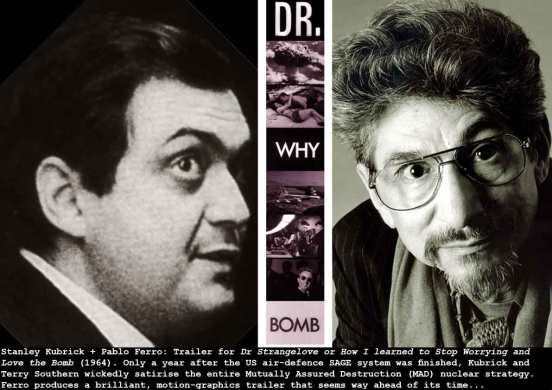

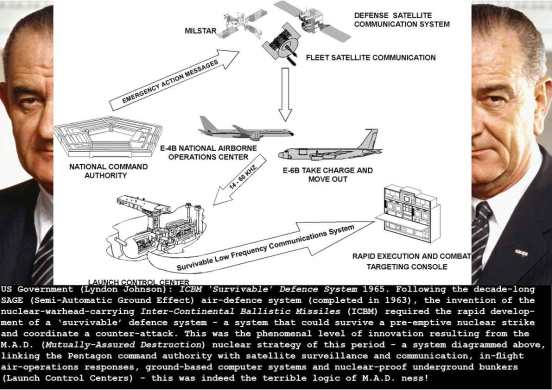

The cold war was peaking in the early 1960s, with a spate of doom-laden novels and films culminating in Harvey Wheeler and Eugene Burdick’s Fail Safe (1962), Kubrick and Southern’s Dr Strangelove (1963) and John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and Seven Days in May (1964) echoing recent real world events like the launch of Sputnik (1959) the Cuba Crisis (1962), the U2 spyplane incident (1960), the assassination of President Kennedy (1963) and the completion of the US SAGE and DEWline early warning system (DEWline 1957, SAGE 1963). The acquisition of information on the enemy by means of spying and surveillance became ever more important. This was confirmed when the Cuba Missile Crisis was precipitated by the photographic evidence of missile installations in Cuba taken from a U2 spy plane. This remarkable aircraft was able to fly above the range of anti-aircraft missiles – at altitudes of 60-80,000 feet, and take photographs of the resolution indicated in the image above.

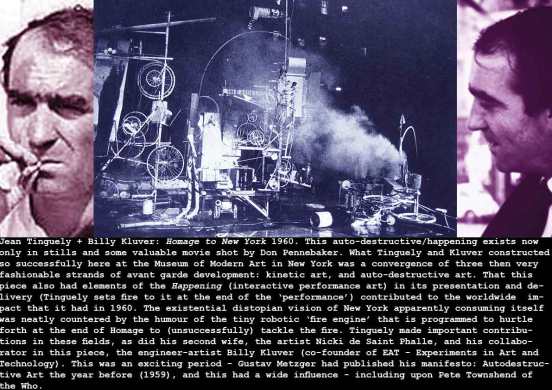

Jean Tinguely + Billy Kluver: Homage to New York 1960

In 1999, I was lucky to see a retrospective exhibition of the work of Gustav Metzger at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford – and as the curator Astrid Bowron points out in the accompanying catalog: “Gustav Metzger is the creator of auto-destructive art and as such, the majority of his work is not merely hard to locate, it literally no longer exists.” And of course this is also true of the great auto-destructive pieces of work by Pete Townshend, Jimi Hendrix and Jean Tinguely – an early exponent of the art, closely following Metzger’s manifesto of 1959. Like Performance art (and great Audio-Visual and Interactive Art) – these pieces only survive in preparatory drawings, eye-witness accounts and archive photos, video or film documentation. Take a look at:

see also Astrid Bowron: Gustav Metzger (1999)

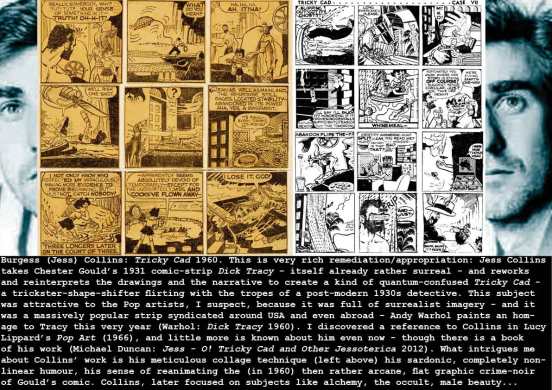

Burgess (Jess) Collins: Tricky Cad 1960

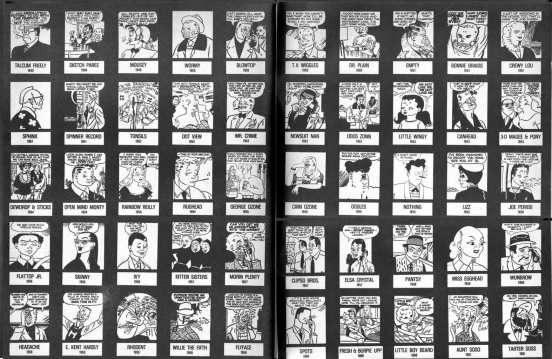

Although the seeds of Pop Art – ‘fine’-art based upon popular culture – had been sown earlier in the century (Janusz Brzeski 1930, Eduardo Paolozzi 1947, Richard Hamilton 1956), the flowering of pop art in America is really a Sixties phenomenon, and here in 1960 we have Jess Collins with his enormously entertaining appropriation, deconstruction and remediation of Chester Gould’s comic strip from the 1930s. Gould’s Dick Tracy reformulated and reconstructed as Tricky Cad, creates a world conceptually even more surreal than the original (Gould was brilliant at inventing hyper-weird villains – see below). I love Gould’s graphic style – the flat, two-dimensional world that he creates with his unbreakable rectangular grid of frames, and I love too the way that Collins recasts these graphic devices into a series of existential excerpts. This body of work easily stands alongside that of the other great narrative collagist of the 20th century – Max Ernst (Les Malheurs des Imortelles 1922, Une Semaine de Bonte 1934, etc).

Chester Gould – a compilation of Dick Tracy villains from mid-1940s to 1960s. The flat, 2d style created by Chester Gould lends itself to apparently limitless invention of surreal characters…

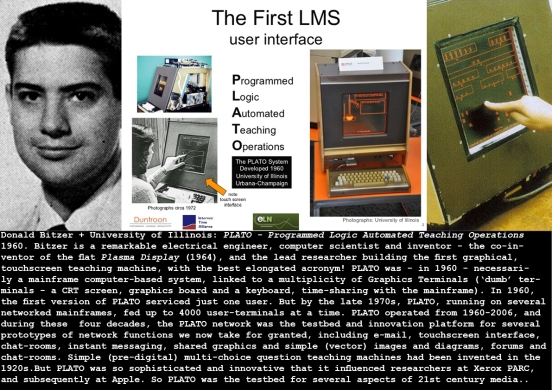

Donald Bitzer + University of Illinois: PLATO – Programmed Logic Automated Teaching Operations 1960

I got really fascinated by the potential of ‘teaching’ machines after I read Buckminster Fuller’s Education Automation (1962), sometime around 1970. PLATO with its accompanying authoring program TUTOR (1969), designed by Paul Tenczar, although main-frame-based and code-formatted (rather than plain English), it was the first attempt at this. As an example, consider:

unit math

at 205

write Answer these problems

3 + 3 =

4 × 3 =

arrow 413

answer 6

arrow 613

answer 12

A TUTOR format program for a lesson in simple arithmetic (from 1973) note that screen coordinates are written as a single number – 413 = line 4, column 13. But otherwise this seems a simple easy-to-learn authoring example. Of course by the time I was able to help develop a learning program – The DTP Graphic Design Mentor in c1989/1990 for the UK Government, we were using C++ to code a hypercard-based structure, and could build sophisticated user-tracking, inference-engines, testing and scoring mechanisms, as well as multimedia questions and learning-frames. In Education Automation, Fuller predicted that education would become the prime world industry, and that schools and universities should capture the best lectures and teaching practice using video and to make these available world-wide (predicting the value of Saul Wurman’s TED Talks (from 1984). And it was the beginning of a vindication of H.G. Wells’ idea for a World Brain (1938), and of Paul Otlet’s vision of a world encyclopedia (The Mundunaeum 1936)

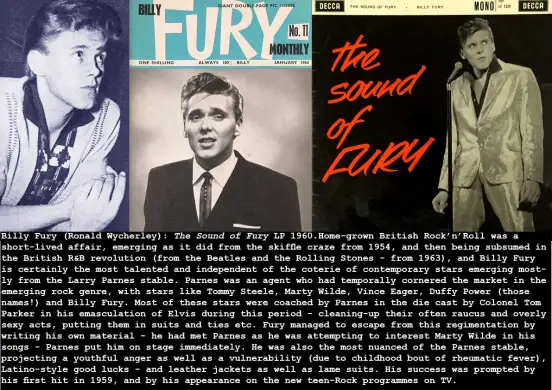

Billy Fury (Ronald Wycherley): The Sound of Fury LP 1960

The official history of Rock’n’Roll in the UK is really the story of older men (like Larry Parnes – spoofed by Val Guest in Espresso Bongo the 1959 film – Laurence Harvey plays the impresario to Cliff ~Richards) – and the record producer Norrie Paramor (Recording director at EMI from 1952). At this time these guys had no vision of what popular music might become in the next decade, rather they modelled their artists/performers on dominant models of success from the previous couple of decades, and by slavishly following the recent commercial developments in the USA – notably Elvis Presley. But there was an undercurrent in British rock’n’roll – a street level awareness of the ‘real’ rock revolution – represented mostly by Americans – Eddie Cochran, Little Richard, Gene Vincent, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis – and also by the rock bands emerging in the UK – Lonnie Donegan, Vince Taylor, Johnny Kidd and the Pirates – at least, those who captured the zeitgeist – the teenage rebellion against the stultifying ‘Fifties, the Suez debacle, years of post-war rationing, the British Nuclear fetish, the thought that everything would go on as before, the greyness of it all. The zeitgeist was reflected on the streets – the Edwardian style Teddy Boys, the British version of the zoot-suit (the drape jackets and baggy trousers with 12″ bottoms, favoured by Teddy boys – the street violence, the Rock riots around Bill Haley’s films (a most unlikely teen hero) these reflected something of the burgeoning teenage angst that was to really erupt in the mid 1960s; there were hints of this in the British teenage films like Expresso Bongo, Beat Girl (a vehicle for Adam Faith – with some interesting period stuff in Soho, St Martins Art School, and the Chislehurst Caves); and the American films: Rock Around the Clock, The Girl Can’t Help It (featuring clips of Fats Domino, Little Richard, Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent!), The Blackboard Jungle, and Alan Freed’s Rock, Rock, Rock (featuring Chuck Berry, Frankie Lyman and the Teenagers, LaVern Baker, and Johnny Burnette, etc).

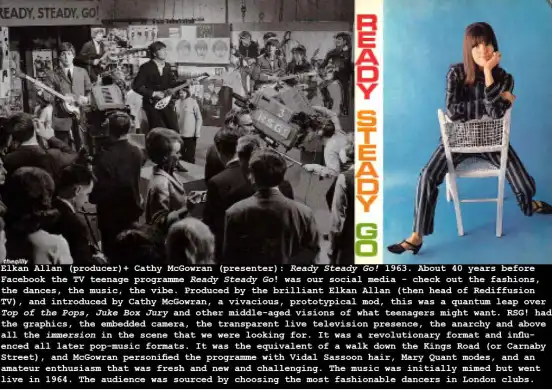

Although mostly typical exploitation films, they captured in part at least some of the zeitgeist – especially in the clips of Little Richard, Fats Domino, Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent etc). Also – television played a big role in the UK providing showcases for local talent and visiting Americans, with the BBC 6.5 Special (1957-1958), then with Jack Good’s revolutionary Oh Boy! (1959) and the BBC’s response Drumbeat (1959). (It wasn’t until Elkan Allan’s Ready Steady Go (1963) that we got a really cool, immersive music show on British TV)

Add to this the tragic death of Buddy Holly, Big Bopper, and Richie Valens in 1959 (I remember the girls gasping and running out of the classroom in tears, on hearing this news at Carisbrooke Grammar School in 1959); Eddie Cochran (age 21 killed on tour in the UK in 1960), and songs like Tell Laura I Love Her (a hit in the UK for Welsh singer Ricky Valence), and you have a cross section sample of the British rock’n’roll zeitgeist – teen rebellion, the skiffle phase, Teddy Boys and bikers, teenage sex, American rock’n’roll, break with the past, some local rock talent (especially Johnny Kidd, Lord Rockingham’s XI, Billy Fury), and of course television and film. (And some of us can add the impact of Ginsberg’s Howl (1955) and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957), and William Burrough’s Naked Lunch (1959) – what a turbulent mix it was!)

For a first-hand account of this zeitgeist in action, you must read Colin McInnis: the London trilogy, City of Spades (1958), Absolute Beginners (1959), and Mr Love and Justice (1960) a trio of coming of age stories set around a Nigerian immigrant; a young photographer; and Frankie Love, a wannabe ponce, all set in London at this time. McInnis gives us the definitive underground portrait of this time.

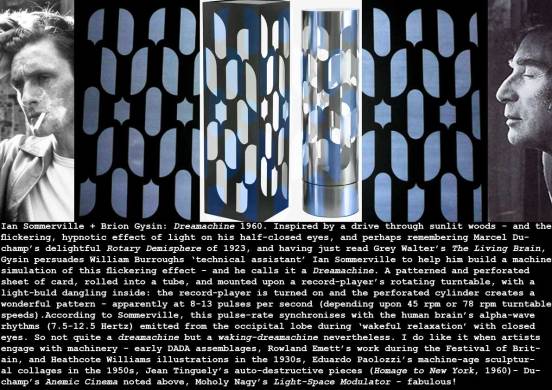

Ian Sommerville + Brion Gysin: Dreamachine 1960

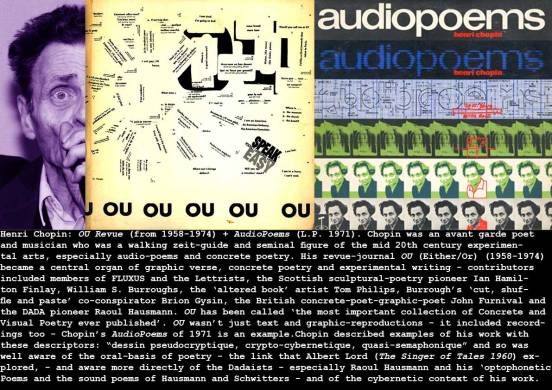

Henri Chopin: OU Revue (from 1958-1974) + AudioPoems (L.P. 1971)

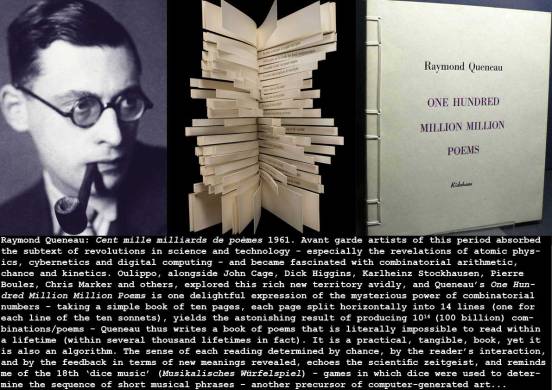

Raymond Queneau: Cent mille milliards de poèmes 1961

I remember showing some students a paper-model I had made of this impossible book – the poem that was physically impossible to read, and the impact that combinatorial numbers made, when you went through the sum, multiplying the number of pages by the number of lines, times the number of permutations in the order of reading – and indeed the significance of the large number (10 to power 14) – sinking in. In my own experience it was like seeing a Möbius strip for the first time, and realising that there was such a thing as a single-sided object – or reading bits of Edwin Abbott’s Flatland – in sum the experience you go through as you re-adjust your thinking and challenge seemingly permanent beliefs is very interesting. Being told of it, then seeing and playing with a paper model of it, constitutes a paradigm-shifting learning experience.

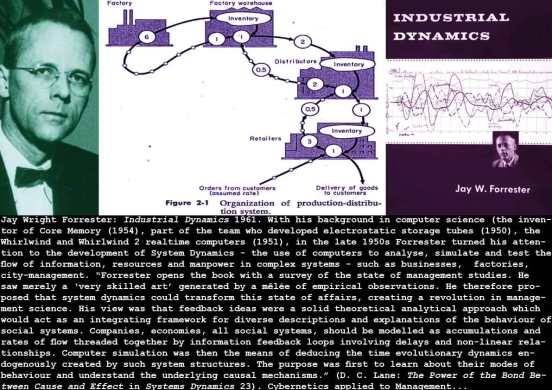

Jay Wright Forrester: Industrial Dynamics 1961

Forrester’s detailed analysis of how complex structures run, how they can be modelled in a computer and how their operations can be simulated and tested under a variety of scenarios – began with Industrial Dynamics and grew to become a sector of study – System Dynamics. By the end of the decade his work had expanded to model the entire world as a simulation – called World Dynamics – or the Limits to Growth model (Forrester 1971). It was Forrester’s paper on Urban Dynamics (1969) – how a city works and can be simulated – that inspired the games designer Will Wright to make his famous Sim-City (1989).

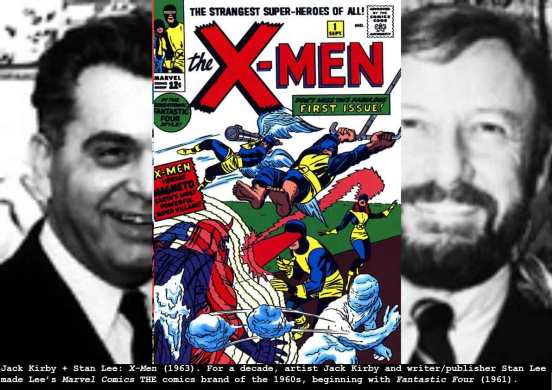

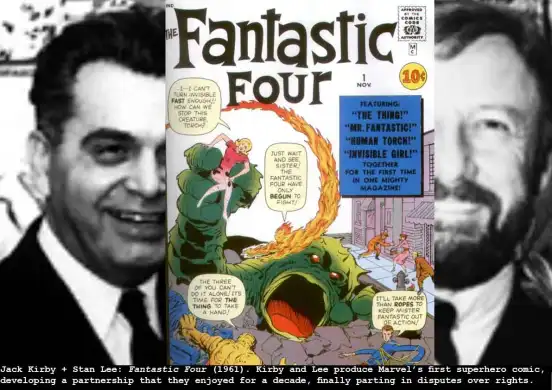

Jack Kirby + Stan Lee: Fantastic Four (1961)

Above all others, Marvel Comics in their Sixties iterations, seemed to punctuate the extraordinary cultural developments in the West with entirely apposite and appropriate versions of old mythologies and their own brand of new myths. From Thor, Asgard and the Rainbow Bridge, to Galactus – the great super-villain – to the The Silver Surfer – that icon of the late Sixties – Stan Lee (working with a number of artists, but predominately with veteran Jack Kirby) repeatedly found the perfect combination of myth, fantasy and graphic style to generate a series of highly successful commercial products that transformed popular culture. Just as Disney in the 1930s and 1940s had remediated and re-interpreted stories from the vast canon of European folk-stories), so Marvel took over this mantel in the 1960s. Marvel were on the zeitgeist button.

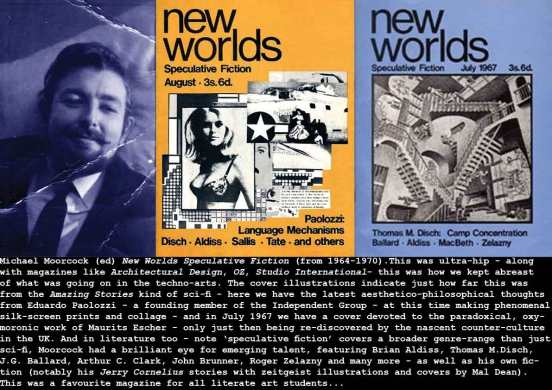

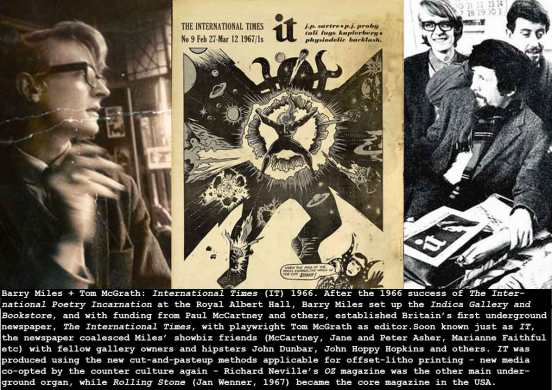

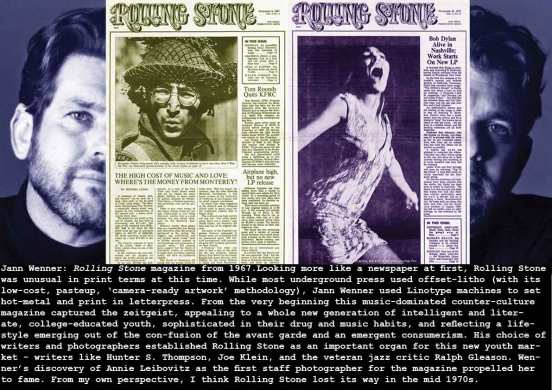

For instance, my favourite reading in the late Sixties and early Seventies included Marvel comics alongside Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds Science Fiction, Theo Crosby’s Architectural Design (AD), New Scientist, OZ magazine, Rolling Stone, Peace News, Studio International and the International Times. But generally, the character development of Marvel – chiefly the work of Stan Lee, collaborating with artists like Jack Kirby, Jim Steranko, Steve Ditko (etc) – was brilliant – both in the sense or being very finely pitched to the developing tastes of Western youth, and in modern myth-making.

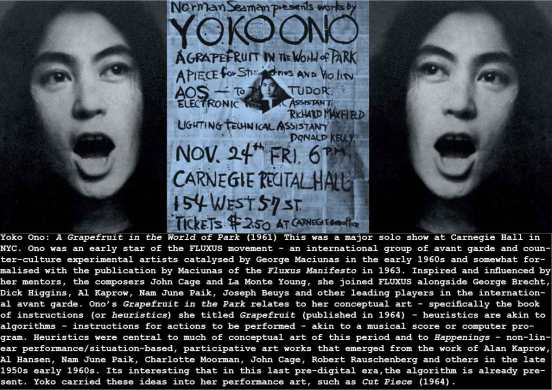

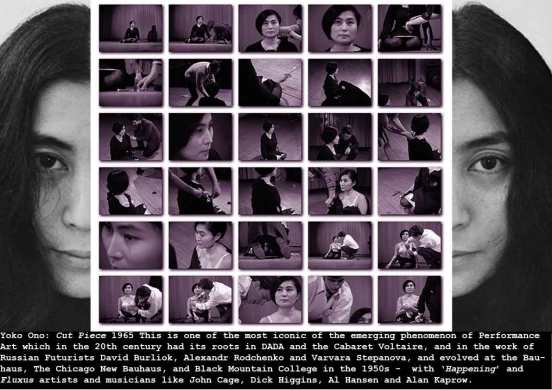

Yoko Ono: A Grapefruit in the World of Park (1961)

Yoko Ono has been centre-stage in the international avant garde since 1961. She broke new ground in performance art, in conceptual art, in intermedia presentation and performance, in event scores, in experimental films, in exhibitions. Her creative and passionate relationship with John Lennon brought her into international focus again from the late 1960s on. I saw her in the Chelsea Arts Club a few years ago, still very stylish and sexy, still cool, still making experimental work – along with her contemporaries Nam June Paik, George Brecht, and George Maciunas she goes into the counter-culture hall of fame.

see: Yoko Ono: Grapefruit (artist’s book) 1964 (republished by Simon and Shuster 2000)

Lenny Bruce: The Carnegie Hall Concert (1961) + What I was Arrested For 1964

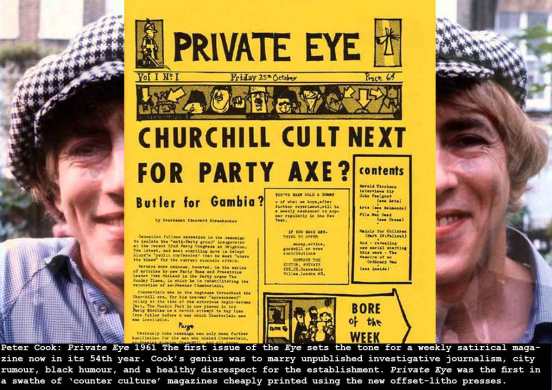

Peter Cook: Private Eye 1961

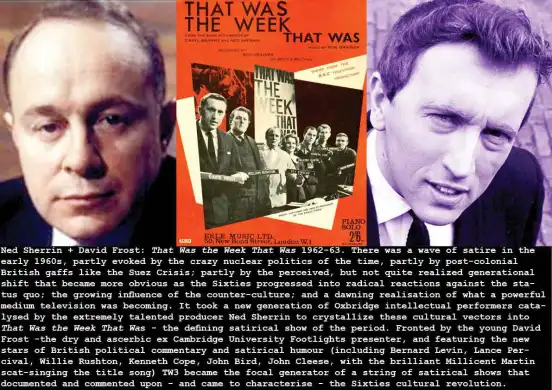

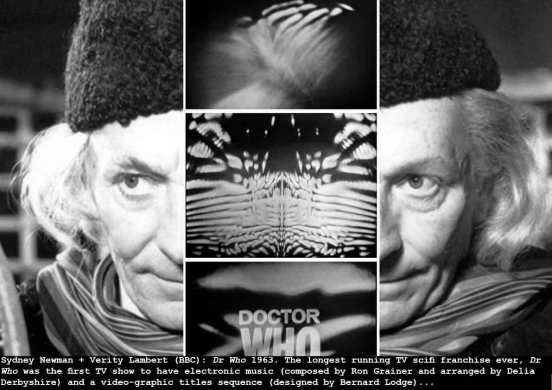

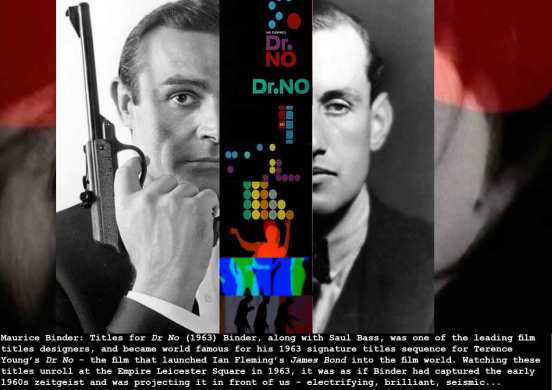

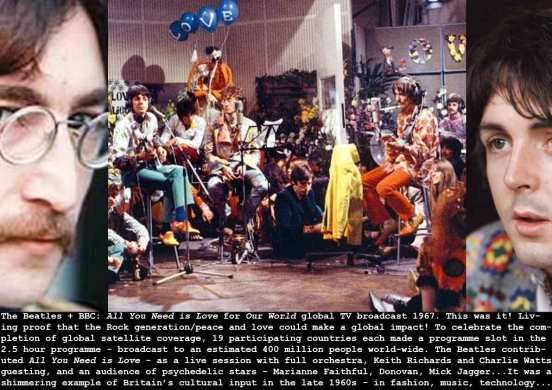

Wow – the early Sixties was fun – Mary Quant launched her Ginger Group in 1963 – lower-priced clothes inspired originally by Chelsea beatniks and bohemians, sold from Bazaar her Kings Road and new Knightsbridge shops; we have the launch of Private Eye (1961); the brilliant Bond films (Dr No 1963), and Dr Who the same year – both with on-the-button zeitgeist titles sequences – graphics that made you sit up and pay attention. And the Beatles and the Stones – the cultural landscape was modulating – rumbling in an earth-quake that would change the world, not just Britain, in the next decade. Here in the early 1960s we began to establish the UK – London especially – as the cultural powerhouse of the whole world. And it was magazines like the Eye, and programmes like TW3 (That was the Week that Was) that kick-started this change. By the end of the Sixties (1967) the Beatles were Britain’s contribution to Our World – the first world-wide Television satellite link-up, singing All You Need is Love. But in the early 60’s it was the biting satirical wit of Frost, Levin, Bird, Martin and the others on TW3, and the ascerbic Private Eye that were the world-changers. (In 1969, I was tickled pink to find a quote of mine – about the IOW Dylan festival ‘being an instant electronic city’ – in the Eye’s Pseud’s Corner).

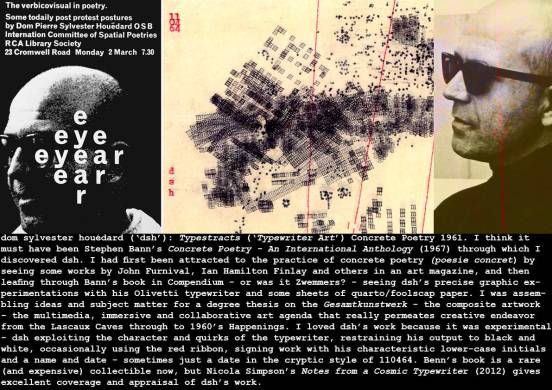

dom sylvester houédard (‘dsh’): Typestracts (‘Typewriter Art’) Concrete Poetry 1961

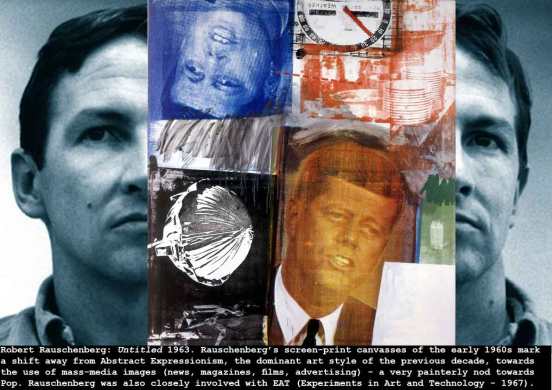

This vibrantly exciting period, when you’re a teenager just discovering all the exciting things that artist’s have done – and are doing right now! – imbued me with a love of the experimental, the avant garde, the counter-culture (though then it was called the Underground). I had been sharing the rare copies of anything by Jack Kerouac and the Beats with friends. We had swopped blues and folk records. I had bought a copy of Stockhausen’s Gesang der Junglinde, was discovering the Independent Group, British pop art and Robert Rauschenberg, Jean Tinguely. – So, discovering the wonderful variety in the convergence of visual art and poetry – by browsing in College libraries, in hipster bookshops – especially Better Books, Zwemmers, Compendium, in magazines like Studio, and in underground press publications like International Times, and Oz, – this became a major influence – the marriage of the senses and the intellect! I loved it. Then I came across an article about Concrete Poetry – an art-form that seemed to have sprung-up – or perhaps ’emerged’ from avant garde poets as far apart as France and South America. So, the typographic experiments of Guillaume Appolinaire, and the photo-montage and collage-typography of the Futurists, DADAists – and especially the sound poems or Ursonate of Kurt Schwitters. Then in the 1950s the emergence (and naming of ) ‘concrete poetry’ in Brazil – with the De Campos brothers, Ferreira Gullar and several others. In 1962 Houedard and other art-poets in the UK, including Ian Hamilton Finlay, John Furnival, Bob Cobbing (etc), took an interest in Concrete Poetry, and developed it into a multimedia fusion of work – in stone, on record, in film, as print, as typo-illustration (Furnival). The traditional or conventional borders of the specialist arts began to break-down in this period – a foretaste of the digital convergence revolution to come?

Nicola Simpson: Notes from a Cosmic Typewriter 2012.

Emmet Williams (ed) An Anthology of Concrete Poetry 1967

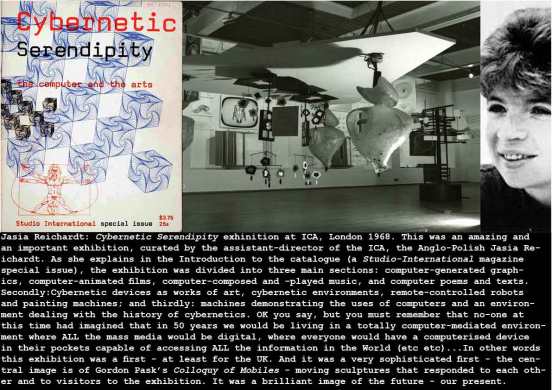

Jasia Reichardt: Cybernetic Serendipity 1968

Jamie Hilder: Designed Words for a Designed World: The International Concrete Poetry Movement, 1955-1971 2016

Designed Words for a Designed World: The International Concrete Poetry Movement, 1955-1971

Karel Zeman: The Fabulous Baron Munchausen 1961

Zeman’s films were a late discovery for me, alas. But the information network catches up with everything in the end, and here he is – possibly the greatest experimental film-maker of mid-20th century – making a series of tour-de-force movies combining live-action, special-effects, animation, photo-montage and more – and as Terry Gilliam points out, achieving a superb, breath-taking visual coherency despite this range of techniques and the juxtaposition of historical styles – 18th century costume + fifties space-suits. I love Gilliam’s notion that this imbues his work with a child-like magic, akin to our discovery of picture books as children, of making model-airplanes, of playing toy theatre, of modelling in coloured plasticene, of meccano, of lego – or just building sand-castles on Colwell beach. Zeman invites us in to play with and enjoy his toybox, and the projected magic of his visions. Terry Gilliam of course, in 1988, revisited the subject in his equally impressive The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, starring the blissful John Neville as the Baron, and capturing something more of the original – the real Munchausen, much given to hyperbolic, imaginative retelling and spinning of his real-life adventures in Muscovy and the Ottoman Empire in the 1730s and 40s.

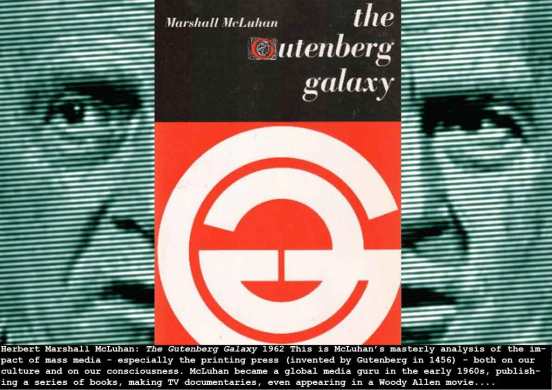

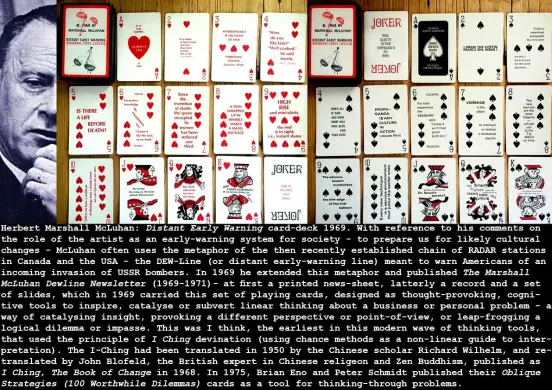

Herbert Marshall McLuhan: The Gutenberg Galaxy 1962

I discovered Elizabeth Eisenstein’s encyclopedic book on the impact of Print (The Printing Press as an Agent of Change 1980) twenty years after I read McLuhan’s Gutenberg Galaxy – but this was the book for this time, reminding us not only of the many physical cultural changes wrought by Print, but of the psychic re-orientation and wholly new methodology of thinking that it precipitated – as McLuhan explains in his Prologue, the reorientation from oral society to typographic society had profound effects, the idea of rote learning, the development of linear step by step logic, – creating the modern scientific revolution; and the leap into someone-else’s personal perspective fostering individuality, the system of visual (vanishing-point) perspective, the Renaissance as books spread knowledge throughout the West in the vernacular, outside the control of State or Church. The Gutenberg Galaxy itself provides the prologue for an understanding of how electronic media is impacting on all these aspects of our culture and our psyche. Read McLuhan’s final section: The Galaxy Reconfigured, then go on to read his Understanding Media (1963).

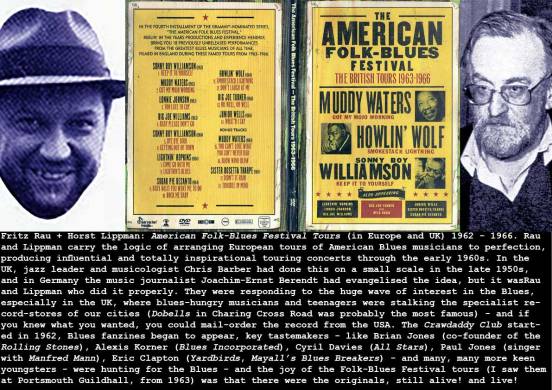

Fritz Rau + Horst Lippman: American Folk-Blues Festival Tours (in Europe and UK) 1962 – 1966.

It’s hard to relate just how thrilling – and how revelatory – these tours were. To see the guys (mostly guys) you had only heard on a sometimes scratchy LP or 45rpm single (the Pye R&B Label was great for the Blues) – to see Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee, Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, Lightnin Hopkins, Howling Wolf – to be there when they were there – to get a taste -however remote – of the juke-jive venues of the late 1940s – only a decade or so previously, but a world away in terms of culture – no race music here thank God – was not only a thrill, but a realised dream. Poring over blues and early jazz records in Collets or Dobells – surrounded by the mystery of early album sleeves, names you didn’t know – and what’s more didn’t know how to find out more about – 30 years before the WWW made this easy. And suddenly here were these legends in the flesh – the cool and the occasion of it!

https://archive.org/details/AmericanFolkBluesFestivals19631966TheBritishTours

Ned Sherrin + David Frost: That Was the Week That Was 1962-63

Live Television in the UK in the early 1960s – paired with innovative sci-fi like Doctor Who, and the essential immersive quality of embedded camera in shows like Ready Steady Go! and TW3, brought a fantastic verve to British broadcasting, celebrating and reflecting the enormous cultural energies bursting out of British culture in this period. And Ned Sherrin assembled a brilliant team to harness and focus these energies for a new, younger, university-educated audience already critical of the status quo, and horrified by the fiasco of Suez, the unquestioning buying-into nuclear power and the Bomb. and the lingering imperialism of Government policy – and all too anxious to support the kind of ascerbic, highly informed, satirical and witty commentary supplied by the likes of Frost, Levin and the rest of the TW3 crew.

Jorge Luis Borges: Labyrinths 1962

There were a number of cultish, must-read authors and books in this period of my life, and Borges was the tops – serious reads with serious mind-bending ideas and fantasies lurking within them. As a marker of this cult status take a look at any of the short stories in this collection – they all reveal virus-like, disquieting, ideas…

Google Books has this to say about Labyrinths:

“Enter Borges’ timeless worlds, where the ideal and the abstract challenge reality; where philosophical paradoxes and endless possibilities abound, and wisps of dream and magic are layered in eternal reoccurrence. To read Labyrinths is to glide through time, space, mythology and philosophy, as Borges’ characters struggle towards devastating discovery. His essays and brief tantalizing parables explore the enigmas of time, identity and imagination. Playful and disturbing, scholarly and seductive, his is a haunting and utterly distinctive voice.”

see also

William Goldbloom Bloch: The Unimaginable Mathematics of Borges’ Library of Babel 2008

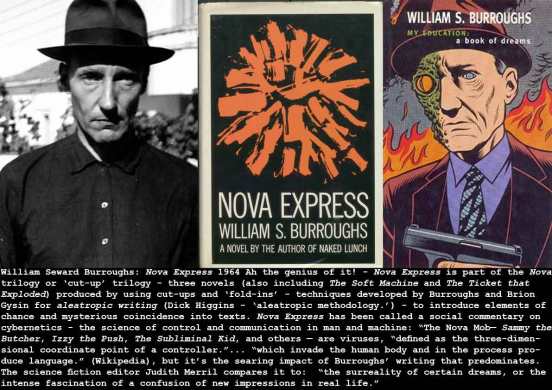

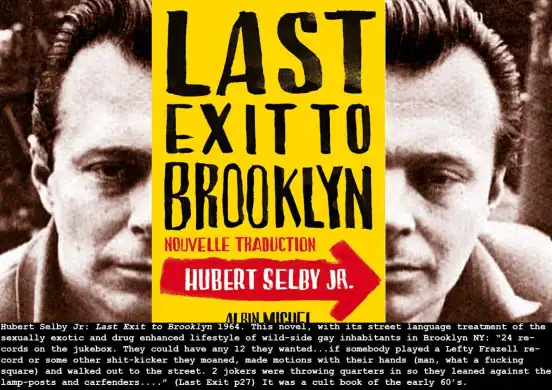

BTW – other cultish books of this period included J.K. Huysmans: A Rebours, books on Alastair Crowley, George Gurdjieff, P.D. Ouspensky; the Ian Fleming Bond novels; the existentialists (Albert Camus especially); the Beats – especially for me Ginsberg’s Howl, Kerouac’s On the Road and The Subterraneans; and Colin McInnes: City of Spades, Absolute Beginners, Mr Love and Justice; Colin Wilson’s The Outsider; Joseph Heller’s Catch 22; Hubert Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn; Jorge Luis Borges’ Labyrinths; William Burroughs‘ Nova Express, Junkie, Henry Miller: Nexus etc...it was a good period…

Joseph Campbell: The Masks of God 1962-1968

I discovered these volumes in East Ham public library, then housed in the Edwardian-gothic town hall building – apparently the building selected by Hitler for his head-quarters after the successful invasion of England in 1941 – and I devoured them all in a frenetic intellectual feast. Campbell wraps his lifetime as a mythographer into these 4 volumes, delving back to primordial times, veering East and West, and covering the last 300 years of recent history in what he called ‘Creative Mythology’ – an examination of archetypal mythic themes treated by modern authors – such as James Joyce: Ulysses and Thomas Mann: The Magic Mountain. If you want a feast that reveals the contiguity and universality of mythic themes (from which Campbell derived The Heroes Journey (1948) then dig in.

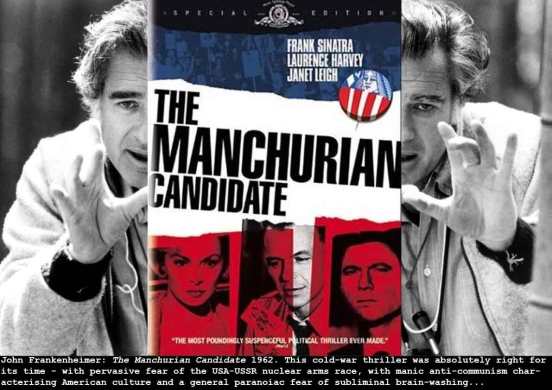

John Frankenheimer: The Manchurian Candidate 1962

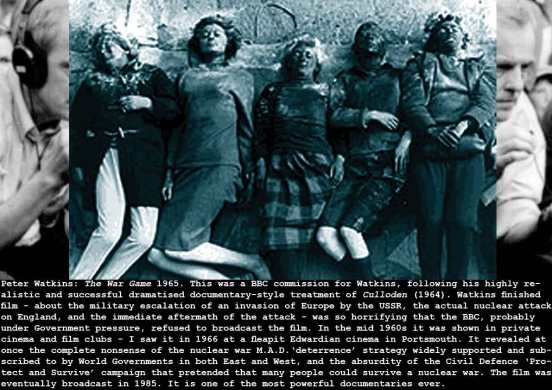

This was particularly good, but there were several notable cold-war movies in this period, movies that summed the bleak Mutually Assured Destruction tension of the NATO/USSR nuclear arms race. My other favourites include Kubrick’s black comedy Dr Strangelove (1963); the same terminal message in Sidney Lumet’s humourless Fail Safe (1964) Sidney Furie’s Ipcress File (1965), Martin Ritt’s The Spy who came in from the Cold (1965); John Sturges: Ice Station Zebra (1968), Norman Jewison: The Russians are Coming, The Russians are Coming (1966), Hitchcock: Torn Curtain (1966); Peter Watkins realistic fake documentary: The War Game (1965) and of course Terence Young’s snappy and stylish Dr No (1962).

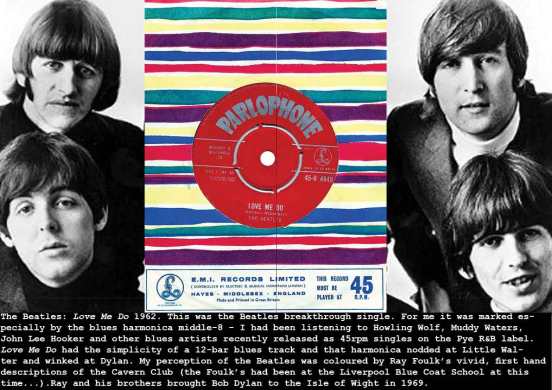

The Beatles: Love Me Do 1962

The arrival of the Beatles in 1962 was different. Previously the teen-age record market had been controlled by old men – men who packaged and represented the artists they managed in order to fit them into a model of the recording/entertainment business that had emerged 50 years previously. ‘The manager/Record Company knew best’ was the mantra – never more obvious than in the way that Elvis Presley had been emasculated and culturally deodorised by Col Tom Parker. The Beatles were to shuck-off this modus-operandi gradually over the next half-decade, seizing creative control of their talent and effectively by the end of this decade doing exactly what they wanted. It was a mark of their exceptional individual and corporate characters and seemingly boundless talent that they survived the Brian Epstein be-suited period, and became themselves again, in the meantime changing the record business for a decade or so…

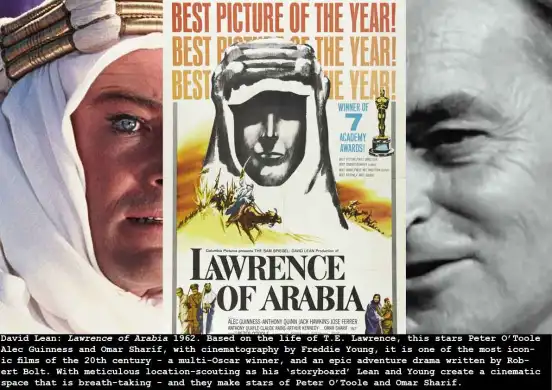

David Lean: Lawrence of Arabia 1962

Joshua Klein has this to say about Lawrence of Arabia: “One of the greatest epics of all time, Lawrence of Arabia epitomises all that motion pictures can be. Ambitious in every sense of the word, David Lean’s Oscar-winning masterpiece, loosely based on the life of the eccentric officer T.E. Lawrence and his campaign against the Turks in World War 1, makes most movies pale in comparison. and has served as an inspiration for countless film-makers, most notably technical masters like George Lucas and Steven Speilberg.” (Joshua Klein in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die 2002)

For me this vies closely with Doctor Zhivago (1965) as Lean’s best work – Freddie Young’s cinematography is absolutely top-notch in both films, as is Maurice Jarre’s composition, and Robert Bolt’s screenplay-writing. But its the cinemascope projection and instant immersion in this film that permeates my memory of seeing it in 1960 – the wonderful location-scouting, the cinematography, the beauty and faux-aristocratic eccentricity of Peter O’Toole (playing Lawrence), the vision of how a colonial army interfaces with Arab tribal politics and the personal honour of the singular men involved (Alec Guiness plays Prince Feisal, Jack Hawkins General Allenby) and the long panoramic shots of the wavering-light and shimmering illusions of the Negev desert!

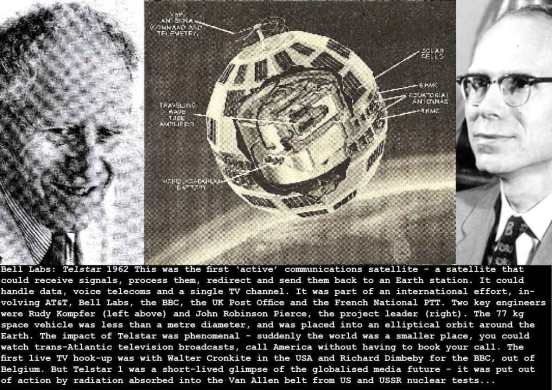

Bell Labs: Telstar 1962

So – 17 years after Arthur C. Clarke’s famous prediction of ‘extra-terrestrial relays’ (later known as communication satellites) Telstar appears – an iconic indicator of the future, and the world gets smaller. McLuhan’s predicted ‘global village’ comes a step nearer. And Telstar was a decade before microprocessors were invented! It was built using the current integrated circuit technology, and able to receive, process, relay and re-broadcast analog television signals, indicating the potential of Arthur C. Clarke’s 1945 prediction – world-around communications links. Buckminster Fuller’s Spaceship Earth was getting wirelessly interconnected….

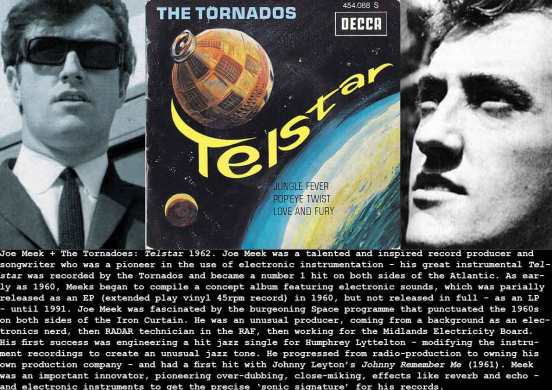

Joe Meek + The Tornados: Telstar 1962

Bob Dylan: Bob Dylan LP 1962

British Art Colleges in the 1960s were important for fostering creativity in design, in art, in performance, in fashion, and many other aspects of our cultural lives. Roy Ascott and others were experimenting with the way Art Colleges work (Ascott: Ealing Ground Course 1962). For myself and many others, art colleges were also our social media – they were where we met our contemporaries, where we saw how others lived, worked and had fun. Attending Portsmouth Art College in 1963, I met several fellow travelers who became lifelong friends – and one of them (Pete Harris) loaned me some of the zeitgeist albums of the period – Carolyn Hester: Carolyn Hester, Joan Baez: Joan Baez, and another self-titled LP: Bob Dylan: Bob Dylan. In one generous step, Harris had brought me up to speed with the folk-revolution that had been emerging in the USA over the previous few years. He also loaned me two Blues albums: Folkways The Country Blues (1959) – a compilation of leading Mississippi Blues artists recorded in the 1930s and 1940s by Sam Charters, and an album of Leadbelly’s work recorded by John and Alan Lomax in the 1930s and 1940s These were all inspirational albums for me, but Dylan’s was the revolutionary one- a revolution in folk-singing that was fresh, angry, sardonic, saucy – Baby Let Me Follow You Down, Pretty Peggy-O, Man of Constant Sorrow, House of the Rising Sun – Dylan brought new interpretative life to these classics – classics which Dylan had picked up over long evenings listening to Carla and Suze Rotolo’s record collection that included Folkway’s Anthology of Folk Music, Blues albums, records by Ewan McColl, Woody Guthrie, and A.L Lloyd – ie the canon of British-American folk music at the time – the expected repertoire of a folk singer. Dylan re-interpreted, not to say personally appropriated these songs in the early Sixties.

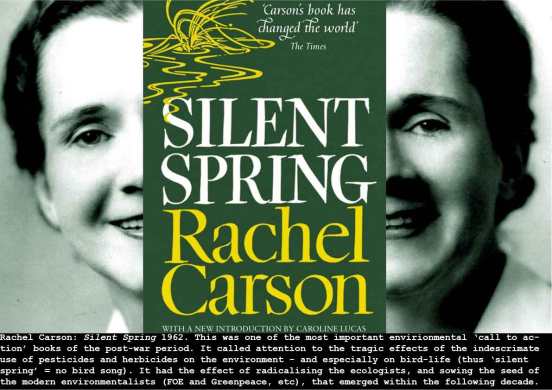

Rachel Carson: Silent Spring 1962

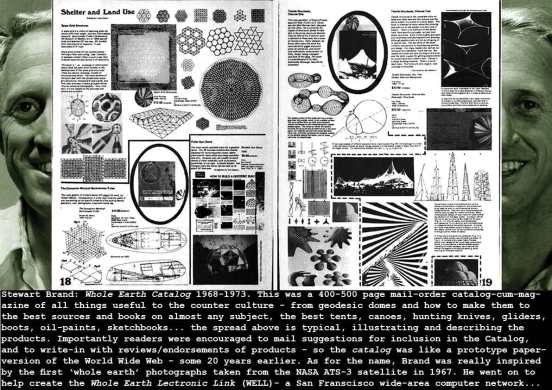

There seem to me to be several key-moments in the Sixties awakening to the environmental problems we were (seemingly unknowingly) stacking up – the use of DDT and other insecticides, over population, depletion of resources, intensive farming, over-fishing, pollution, (etc etc). And this was the first in this important decade – the decade that ended with us leaving Earth for the first time, and experiencing that revelation that we were just one tiny blue planet of Life in a universe of blackness. The next key moment was the picture of the ‘whole Earth’ sent back by the NASA ATS-3 satellite in 1967. This impacted upon us – who Buckminster Fuller had described as ‘crew-members’ of ‘Spaceship Earth’ in all kinds of ways – inspired by this picture, Stewart Brand founded his Whole Earth Catalog (1968) – a mail-order catalogue of sustainability and alternative life-styles. Then the powerful activist world Environmental movements were established – Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth leading the way in the late 1960s -early 1970s. But it was kick-started by Rachel Carson.

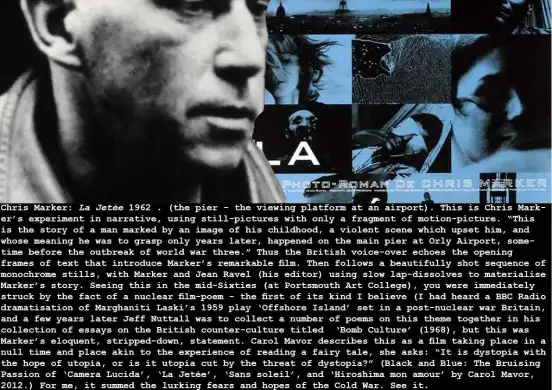

Chris Marker: La Jetée 1962 Chris Marker: La Jetée 1962

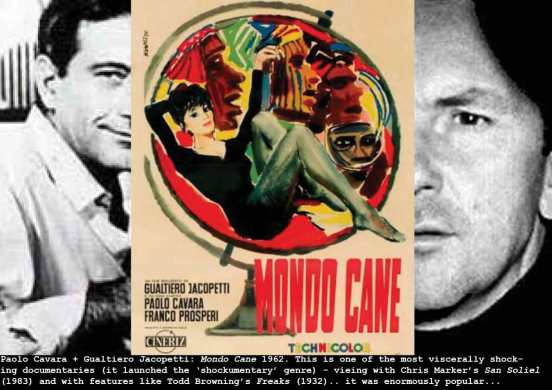

Paolo Cavara + Gualtiero Jacopetti: Mondo Cane 1962

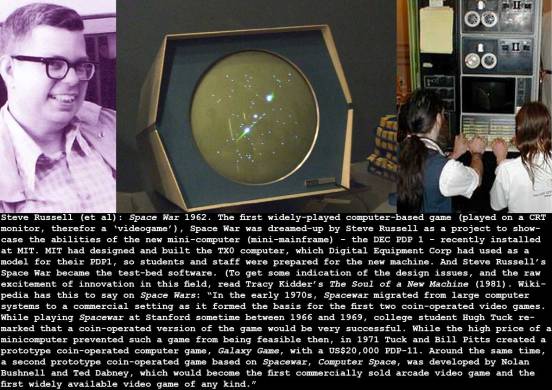

Steve Russell (et al): Space War 1962

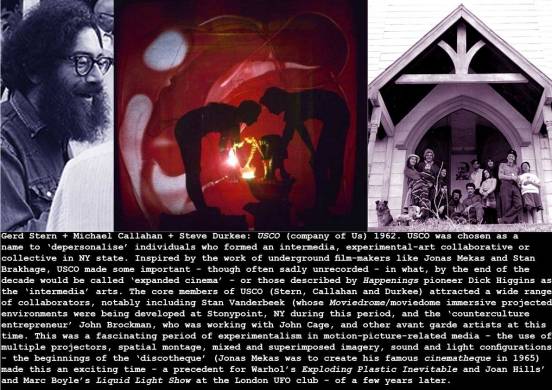

Gerd Stern + Michael Callahan + Steve Durkee: USCO (company of Us) 1962

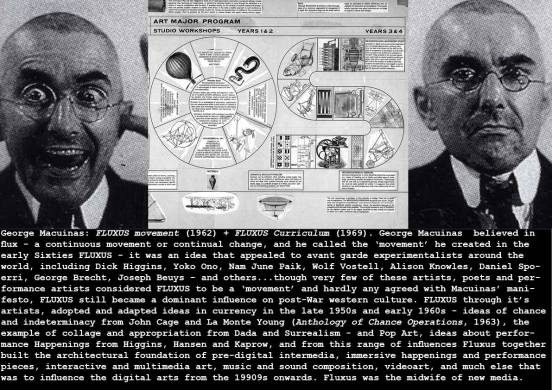

George Macuinas: FLUXUS movement (1962) + FLUXUS Curriculum (1969)

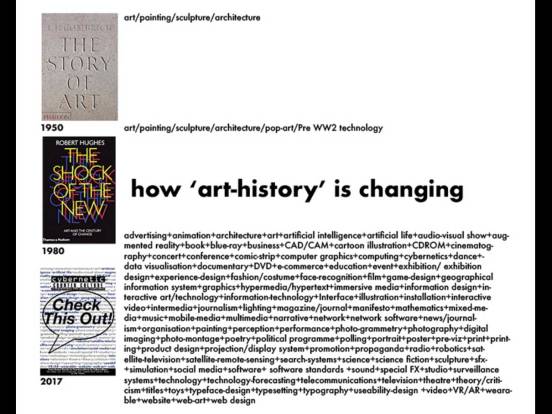

You can see from these last few entries that some of the principal strands of 21st century media – video-art, experimental film, computer games, intermedia art – were emerging in the early 1960s. Fred Turner in his The Democratic Surround – Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties (2013) has mapped the progression from the military technologies of WW2 and after through the 1950s and artistic experiments with these technologies, (audio-tape, transistor, computer, analog gun-controllers, cybernetics, machine intelligence, computer-generated music, poetry, and art etc) often by artists in the ‘underground’ or counter culture sector. Fluxus epitomised and catalysed this fusion of high-tech and art-experiment. Macuinas also made important inputs to the ongoing debate about art education and the art-school curricula. In the UK, this was very relevant at this time, following the William Coldstream report (1960) that launched the new modernist ‘Diploma in Art & Design (DipAD), with its contemporary rationalisation of the Gropius’ Bauhaus curriculum. This debate is being revisited in the 21st century, as it dawns on the world that ‘art and design’ is absolutely as central to innovation in new media as is computer science and coding. As I pointed out at an RSA meeting recently, Art history is changing:

and now includes the entertainment arts, the counter-cultural experiments of the 20th century, cybernetic and digital-media arts, the content-creation arts of the 21st century, and much more. It’s thanks to the great innovations of Gropius, of Moholy Nagy, of Black Mountain College, of Coldstream, of Roy Ascott, Richard Hamilton and Victor Pasmore – and of all the experimental art-educator’s of recent times, that the model for 21st century art-education is still evolving.

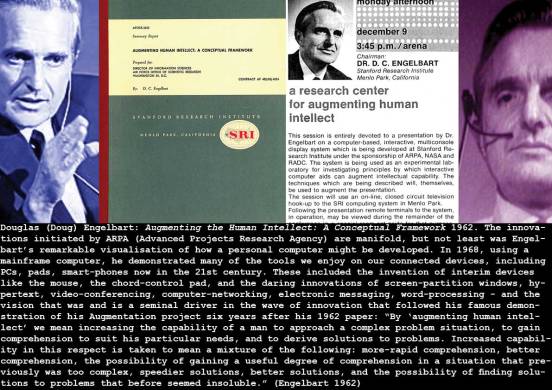

Douglas (Doug) Engelbart: Augmenting the Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework 1962

Engelbart continues his Introduction to AUGMENTING HUMAN INTELLECT : A Conceptual Framework. October 1962: “And by “complex situations” we include the professional problems of diplomats, executives, social scientists, life scientists, physical scientists, attorneys, designers — whether the problem situation exists for twenty minutes or twenty years. We do not speak of isolated clever tricks that help in particular situations. We refer to a way of life in an integrated domain where hunches, cut-and-try, intangibles, and the human “feel for a situation” usefully coexist with powerful concepts, streamlined terminology and notation, sophisticated methods, and high-powered electronic aids.” from http://www.1962paper.org/web.html

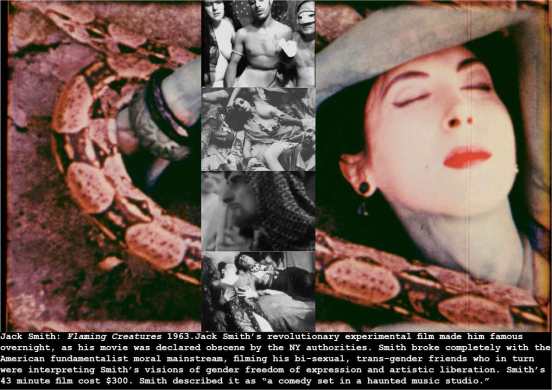

Jack Smith: Flaming Creatures 1963

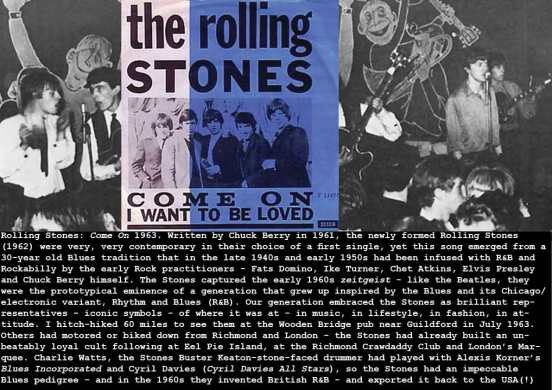

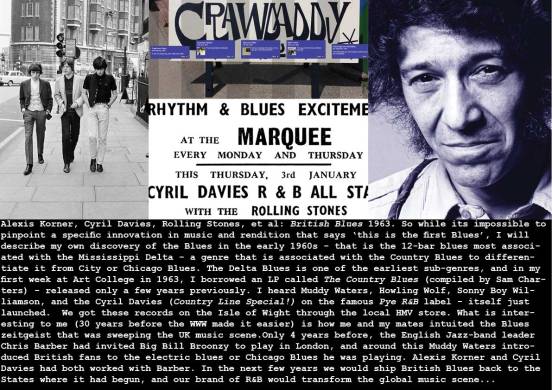

Alexis Korner, Cyril Davies, Rolling Stones, et al: British Blues 1963

- In 1961 the jazz and R&B club Klooks Kleek was founded at the Railway Hotel in West Hampstead – they started regular R&B evenings in 1963.

- In 1962 the first dedicated Blues magazine ‘Blues Unlimited’ was published – a mimeographed (duplicated) newsheet edited by Mike Leadbitter and Simon Napier.

- In 1962 Cyril Davies had formed Blues Incorporated with Alexis Korner, had created the Ealing Club – the first music venue to be totally identified with Rhythm and Blues in the UK (Mick Jagger sang there that year).

Jack Kirby + Stan Lee: X-Men (1963)

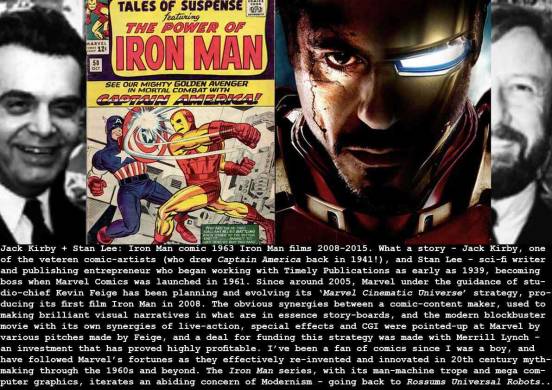

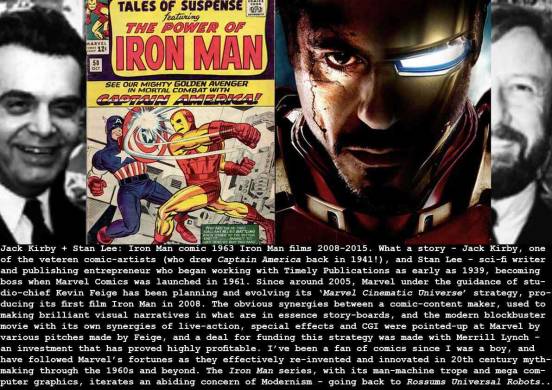

Jack Kirby + Stan Lee: Iron Man comic 1963 Iron Man films 2008-2015

Jack Kirby + Stan Lee: Iron Man comic 1963 Iron Man films 2008-2015. What a story – Jack Kirby, one of the veteran comic-artists (who drew Captain America back in 1941!), and Stan Lee – sci-fi writer and publishing entrepreneur who began working with Timely Publications as early as 1939, becoming boss when Marvel Comics was launched in 1961. Since around 2005, Marvel under the guidance of studio-chief Kevin Feige has been planning and evolving its ‘Marvel Cinematic Universe’ strategy, producing its first film Iron Man in 2008. The obvious synergies between a comic-content maker, used to making brilliant visual narratives in what are in essence story-boards, and the modern blockbuster movie with its own synergies of live-action, special effects and CGI were pointed-up at Marvel in various pitches made by Feige, and a deal for funding this strategy was made with Merrill Lynch – an investment that has proved highly profitable. I’ve been a fan of comics since I was a boy, and have followed Marvel’s fortunes as they effectively re-invented and innovated in 20th century mythmaking through the 1960s and beyond. The Iron Man series, with its man-machine trope and mega computer graphics, iterates an abiding concern of Modernism – going back to Rossums Universal Robots.. And more: Marvel have resolved a modus operandi for generating commercially, aesthetically and technically successful movies based upon their comic-strip stable of superheroes…

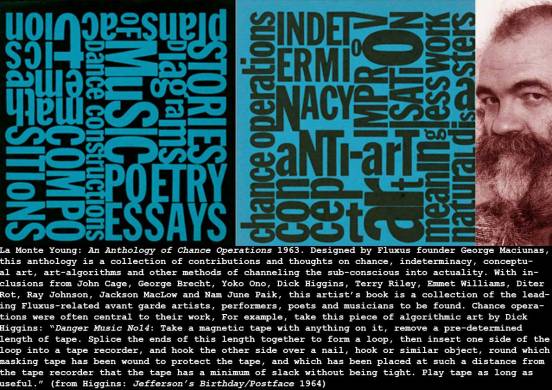

La Monte Young: An Anthology of Chance Operations 1963

La Monte Young was one of the core composers in the invention of the minimalist tradition in serious music studies. And here he includes his contemporaries Terry Riley – another profound influence on minimalism – and of course John Cage – the revolutionary composer of modern music – and the pioneer of multimedia happenings. And here also Nam June Paik – the video-artist inventing new mutimedia art forms; the multi-talented poet- publisher Dick Higgins, the mail-art pioneer Ray Johnson,

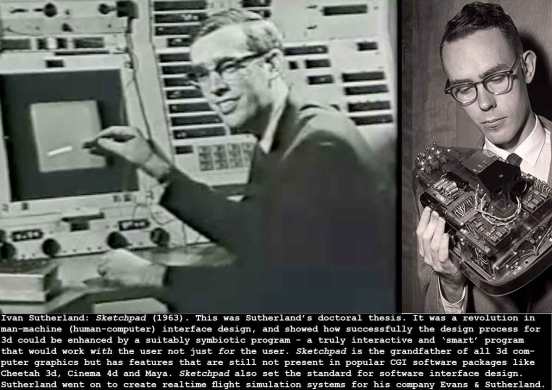

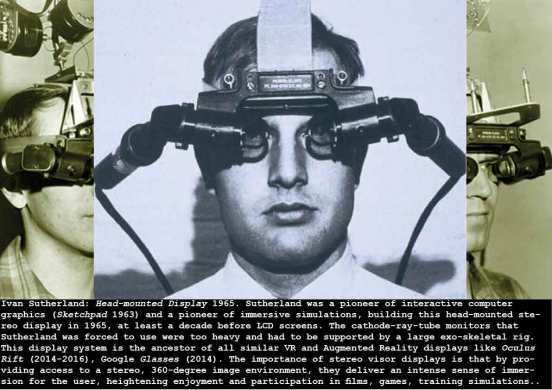

Ivan Sutherland: Sketchpad (1963)

Important computer pioneers like Ted Nelson and Alan Kay write in awe of their first experience of Sutherland’s Sketchpad, while Alan Blackwell and Kerry Rodden of Cambridge University Computer Lab describe it thus:

“Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad is one of the most influential computer programs ever written by an individual, as recognized in his citation for the Turing award in 1988. The Sketchpad program itself had limited distribution — executable versions were limited to a customized machine at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory — so its influence has been via the ideas that it introduced rather than in its execution. Sutherland’s dissertation describing Sketchpad was a critical channel by which those ideas were propagated, along with a movie of the program in use, and a widely-cited conference publication.”

Blackwell and Rodden: Preface to Ivan Sutherland: Sketchpad (Electronic Edition 2003)

There is a video of Alan Kay describing Sketchpad at:

Elkan Allan (producer)+ Cathy McGowran (presenter): Ready Steady Go! 1963

If you lived on the Isle of Wight (as I did) in the early 1960s, you really, really needed information on what your contemporaries in London were up to – what clothes, what hair, what music, what dance, what books, what records, who was cool and who wasn’t – you needed this information in a way that our social media surfeited 21st century youngsters just won’t understand. As I said above – RSG! was our social media, and an important ingredient on that crazy path of learning, learning everything we could, reading as much as possible, searching for guidance, searching for records, for Art, for poetry, for intelligence! OK, RSG supplied social intelligence – and breaking new music – we needed that.

Jack Kirby + Stan Lee: Iron Man comic 1963 Iron Man films 2008-2015

These comics were very important to us in the 1960s – it wasn’t just the superb draftsmanship of Kirby, Steranko and the other artists – or the great storylines of Stan Lee’s editorial office, nor just the innate media characteristics of the comic itself – the glossy cover, the pulp thick newsprint, the quality of the internal printing, the slight mis-registers, the smell of the printed artefact, the heft of it – the small classified-style ads for x-ray specs, see-backro-scopes, and other magical stuff. It was all these things – plus the exciting reinvention and remediation of world mythology, and the invention of new narratives in what Joseph Campbell called ‘creative mythology’. OK I was in my early 20s, but I’d first seen American comics as the colour newspaper comic supplements brought back by my uncle from his National Service army tour in Korea circa 1952. These broadsheet-size supplements had been a revelation of another world – in rationed Britain, the colourful crime, fantasy and sci-fi adventure was a wonderful discovery. (Terry and the Pirates, Steve Canyon, Dick Tracy et cetera all stand out in my memory). I was lucky just to get a taste of the work of the golden-age comic artists – Milton Caniff, Chester Gould, Alex Raymond, Burne Hogarth etc) in their native medium – the newspaper comic preceded the comic-book by many years. And a decade or so later the various Marvel comics, often bought second-hand in book-stores, fitted into the same pleasure-zone. So here I am in my 7th decade enjoying the cinematic remediations with the same glee – and the same critical appreciation of the fine story-telling, the invention of credible and dramatic back-stories, the production values, the CGI animation and special effects, the ideas! the visualisations! and all the other qualities I was gripped by…

Sydney Newman + Verity Lambert (BBC): Dr Who 1963

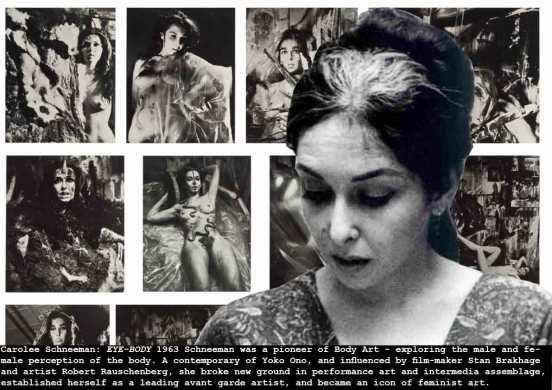

Carolee Schneeman: EYE-BODY 1963

Carolee Schneeman: Meat Joy 1964

Maurice Binder: Titles for Dr No (1963)

As I mention above, if anyone caught the graphic-design zeitgeist better than the film-titles designers of this period, I haven’t come across them. But Maurice Binder on Dr No has to come close to the top. Bernard Lodge on Dr Who was also a key designer of this period (but that was in monochrome – for a 12″ black and white – television), not the Panavision 70mm large colour cinema-screen of the Empire Leicester Square – like a concrete poem writ-large, with John Barry’s arrangement of Monty Norman’s Bond theme in sharp synchrony to the crisp graphics – the whole seamlessly integrated into the beginning of the movie…it was ‘wow!’ it was the business, and announced the Sixties as clear as Ready Steady Go!‘s 54321 titles of the same year…

Robert Rauschenberg: Untitled 1963

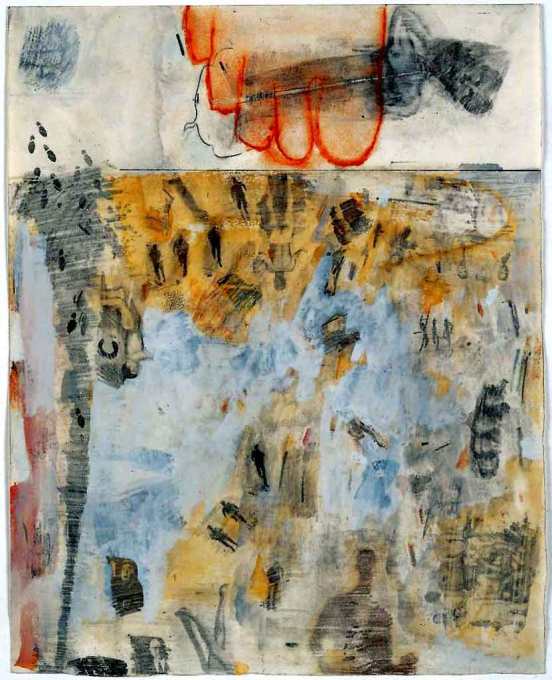

I was lucky enough to see Rauschenberg’s Dante’s Inferno at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1964 – my second year at art school – and it was a revelation. I’d seen repros of his work in art magazines (Studio International was the favorite ‘zine then), but looking at this extraordinary suite of thematically linked drawings-cum-rubbed-off montages – at the subtlety and delicacy of the densely figured images, was a spiritual experience. Rauschenberg – always a formal innovator as well as a brilliant imagist and painter – had evolved a technique of using spirit-based solvent (there was a product called Polyclens that worked) applied to the reverse side of a commercially printed image (from a magazine or newspaper) and then he simply rubbed the reverse side with a burin to create a mirror-image rub-off of the printed image on his drawing paper. This gives you some indication:

Robert Rauschenberg: drawing-cum-rubdown-collage image from Dante’s Inferno 1964

Rolling Stones: Come On 1963

Tony Richardson: Tom Jones 1963

George Maciunas: Fluxus Manifesto 1963

Stanley Kubrick + Ken Adam: Dr Strangelove 1963

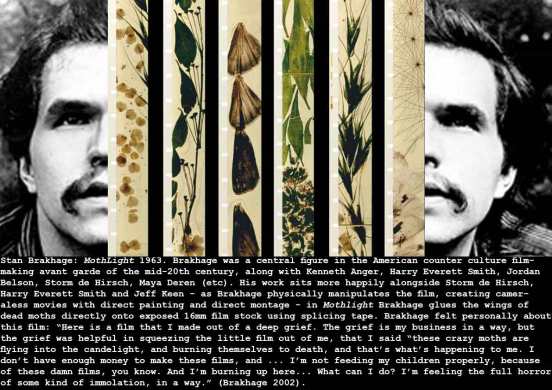

Stan Brakhage: MothLight 1963

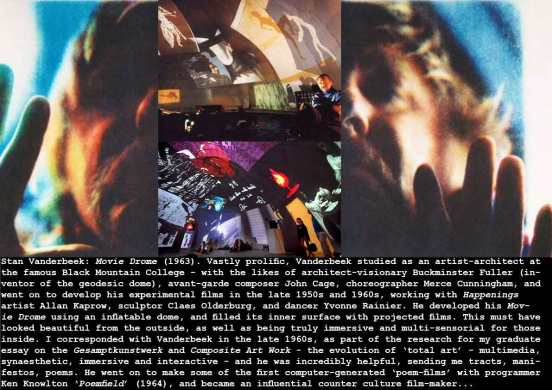

Stan Vanderbeek: Movie Dome (1963)

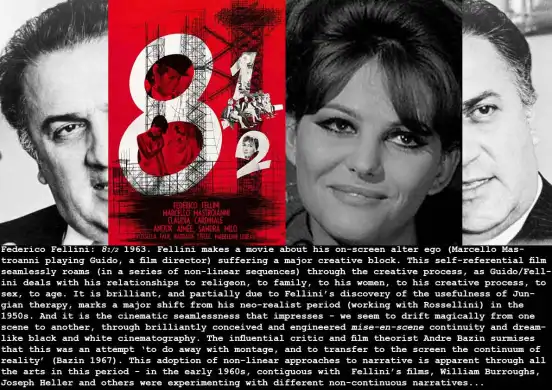

Federico Fellini: 81/2 1963

Abraham Zapruder: Kennedy Assassination 1963

I was in a cool coffee-bar called The Caribou – in Cross Street, Ryde, and had just got back from Portsmouth Art College – when I heard the hastily re-tuned radio replacing the Caribou juke-box. Jesus! Kennedy had been sold to us very successfully (it wasn’t til much later that we realized he had initiated the Vietnam War, about his sex life, and all the other stuff) – then we were immersed in the Camelot vision, so this was a visceral shock.

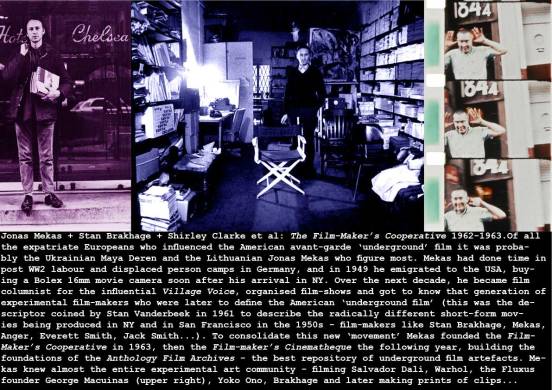

Jonas Mekas + Stan Brakhage + Shirley Clarke et al: The Film-Maker’s Cooperative 1962-1963

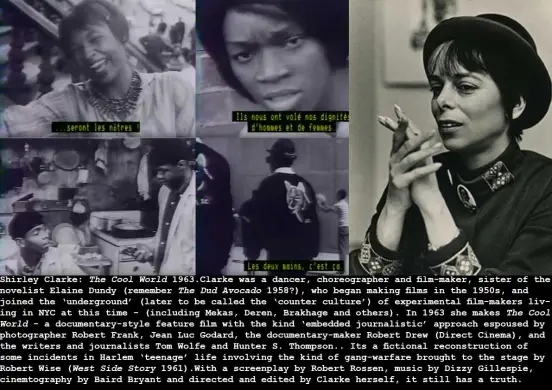

Shirley Clarke: The Cool World 1963

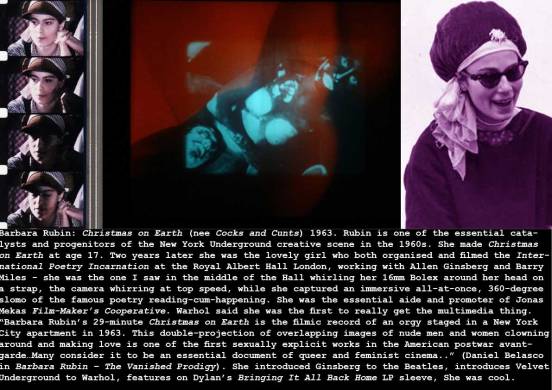

Barbara Rubin: Christmas on Earth (nee Cocks and Cunts) 1963

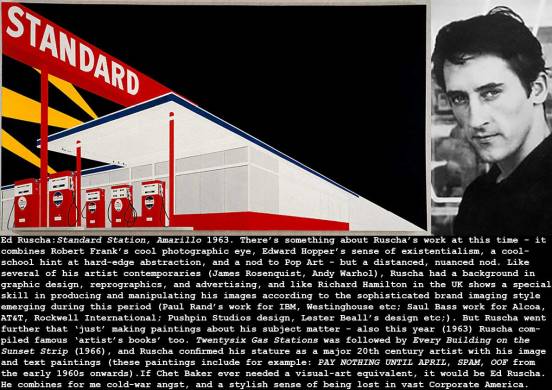

Ed Ruscha:Standard Station, Amarillo 1963.

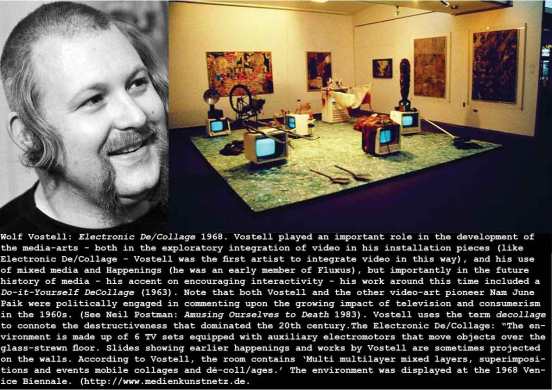

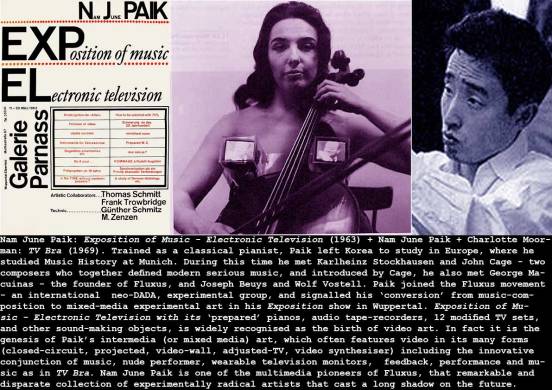

Nam June Paik: Exposition of Music – Electronic Television (1963) + Nam June Paik + Charlotte Moorman: TV Bra (1969)

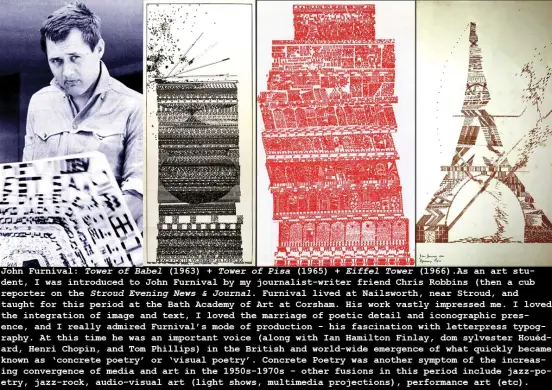

John Furnival: Tower of Babel (1963) + Tower of Pisa (1965) + Eiffel Tower (1966)

I have very fond memories of this period, as I was at art school in Portsmouth, and met two friends (Larry Pryce and David Hill) of the late Chris Robbins, and so spent a fair bit of time in Stroud (Gloucestershire) – Chris’s cottage was in Bagpath. Stroud, then as now a cultural hot-spot – then even more enlivened with ex-patriot Londoners looking for routes out of the rat race. Stroud’s reputation was built upon Laurie Lee of course (his Cider with Rosie was then recently published – in 1959), and he still frequently held court in the Woolpack public house in Slad. Chris Robbins’ job was to cover the entire Stroud area, and part of his journalistic scouting technique was to frequently visit many of the totally charming pubs in the area. Chris also invited his mates to art exhibition openings, private studios (there was a gaslit studio), and poetry-readings. I think I met John Furnival at the Stroud Subscription Rooms sometime around 1966, and certainly became aware of his Tower of Babel and other early works at this time. The Stroud experimental art and poetry scene is still very much alive of course, there is the brilliant Dennis Gould – one of the 1960s Peace News editorial team – still making letterpress pictogrammatic poems and activist statements; (I was at Dennis’ 70th birthday party a few years ago – a pop festival of a party, listening to Adrian Mitchell reading Tell Me Lies about Iraqistan); Helena Petre of the Wild Women of Stroud poets society; Jeff Cloves, the activist and peace poet, and until recently, Leo Baxendale, the anarchist-artist of Minnie the Minx and the Bash Street Kids.

The importance of Furnival and his contemporary poesie concret artists to me was that they were working in this ‘synaesthetic’ sector, blending the visual with literary aesthetics. For me this was a perfect blend – combining the intellect and the sensory – and satisfying both eye and brain.

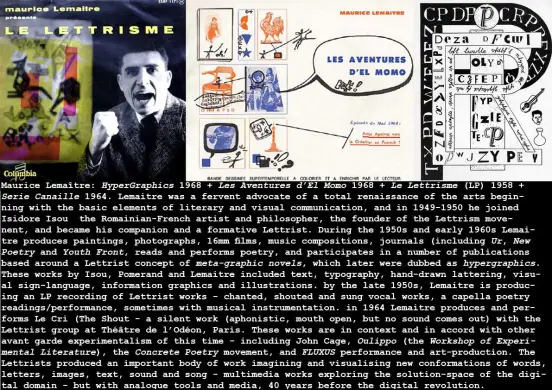

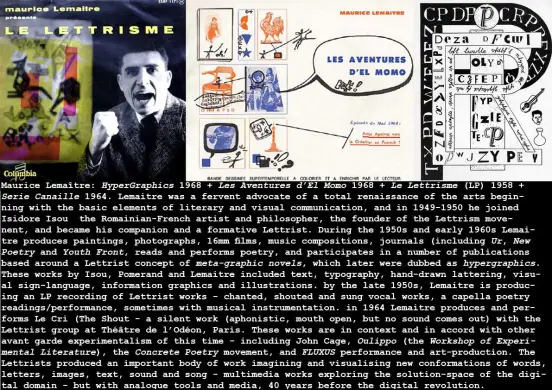

See also Henri Chopin: OU 1958; Tom Phillips: A Humument 1970; dom sylvester houedard: typestracts 1961; Maurice Lemaître: Lettrisme 1968

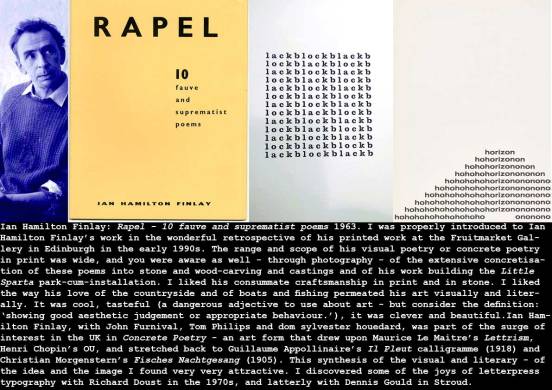

Ian Hamilton Finlay: Rapel – 10 fauve and suprematist poems 1963

Around this time I was introduced to Christopher Logue and the Tony Kinsey Quartet’s Red Bird Dancing on Ivory (1959) – the first jazz-poetry record I came across, so seeing artists and poets exploring the graphic realisation of poems seemed very a propos! (in the 1990s, wandering around the Fruitmarket Gallery, another visitor was Christopher Logue. Lately, I can see that the fusions and confusions of form and content, of idea and image, of sound and word were perhaps spirit of the age pointers to the eventual digital fusion of all analogue forms…

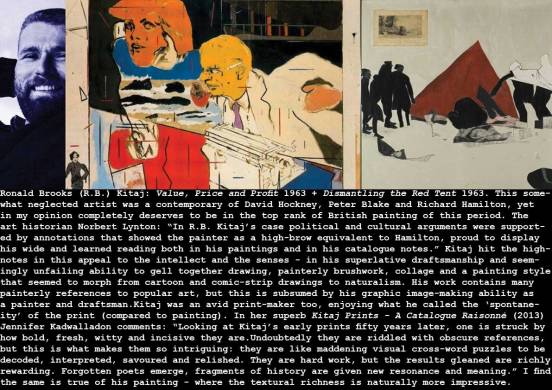

Ronald Brooks (R.B.) Kitaj: Value, Price and Profit 1963 + Dismantling the Red Tent 1963

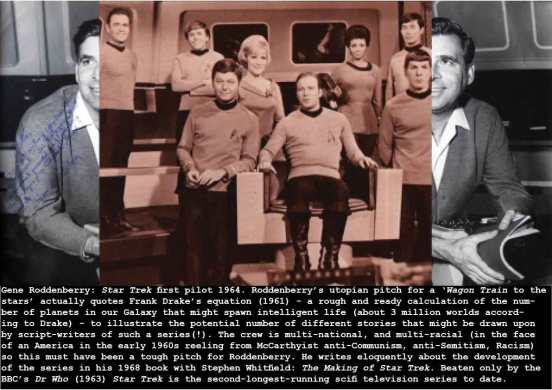

Gene Roddenberry: Star Trek first pilot 1964

I enjoyed the sometimes very familiar tropes and ideas given new life in the Star Trek series – some very good sci-fi was aired here, but it wasn’t until I read Roddenberry’s book on the genesis of the series (Roddenberry: The Making of Star Trek (1968) that I grasped its true import – nothing less than a sincere attempt to create a kind of utopian ideal for our potential future in space – Roddenberry’s vision of a mixed-race (mixed-species!) crew must have been a hard-sell to an American mainstream media outlet conditioned by a decade of McCarthyism, anti-semitism, racism, mistrust of the left etc..That he succeeded in making his idea work – and work so successfully over the next several decades – is remarkable.

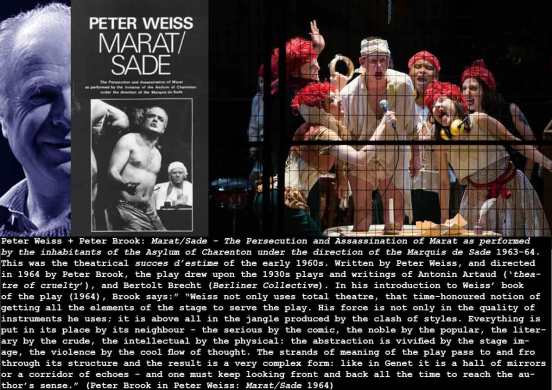

Peter Weiss + Peter Brook: Marat/Sade – The Persecution and Assassination of Marat as performed by the inhabitants of the Asylum of Charenton under the direction of the Marquis de Sade 1963-64.

Translated by Geoffrey Skelton and Adrian Mitchell, the book of the play was published in English in 1964. The back cover comments included: “The RSC’s work in establishing Antonin Artaud’s conception of ‘ the Theatre of Cruelty‘ found its climatic expression in this powerful and savage play, in which the discipline of verse heightens the emotional impact, and the combination of sheer entertainment, Sadian philosophy and the range of theatrical shock techniques leaves the audience limp but excited at the end of the evening. The published text allows the reader to see how skilfully the author has dramatised the paradox of de Sade, a black saint whose humanity must be set against there horrors of his imagination” (cover notes Peter Weiss: Marat/Sade 1964)

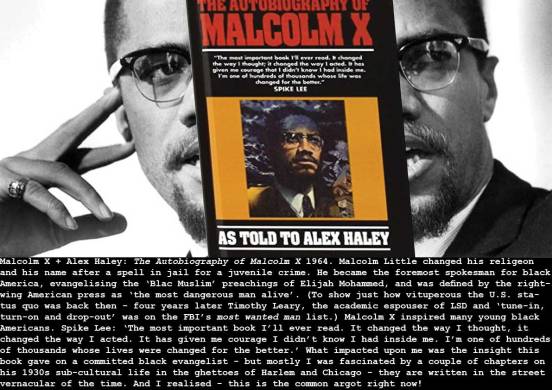

Malcolm X + Alex Haley: The Autobiography of Malcolm X 1964

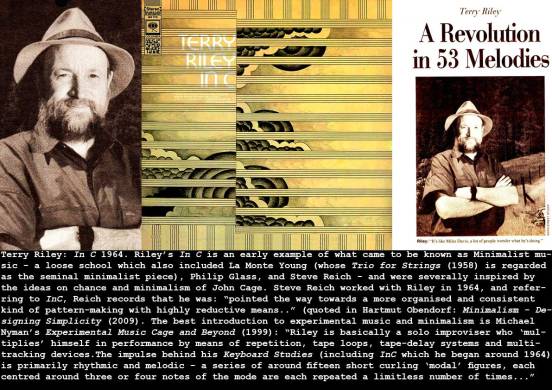

Terry Riley: In C 1964

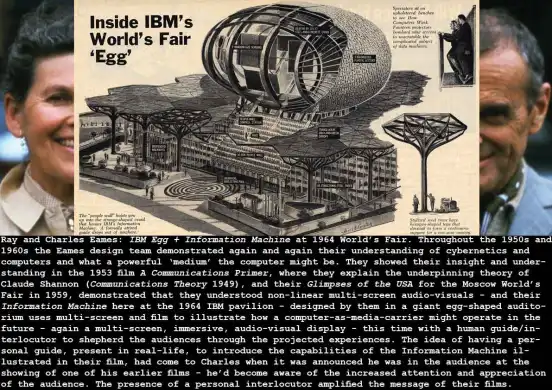

Ray and Charles Eames: IBM Egg + Information Machine at 1964 World’s Fair

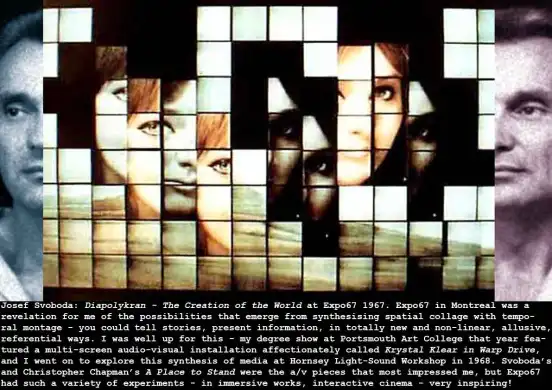

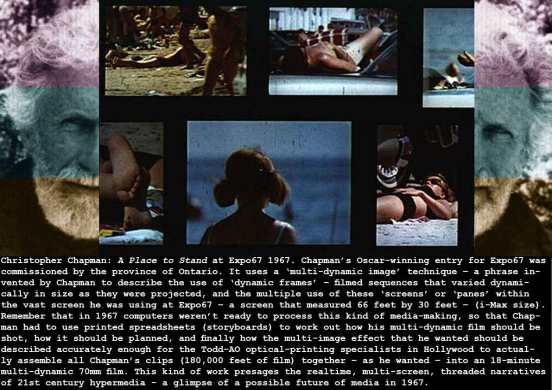

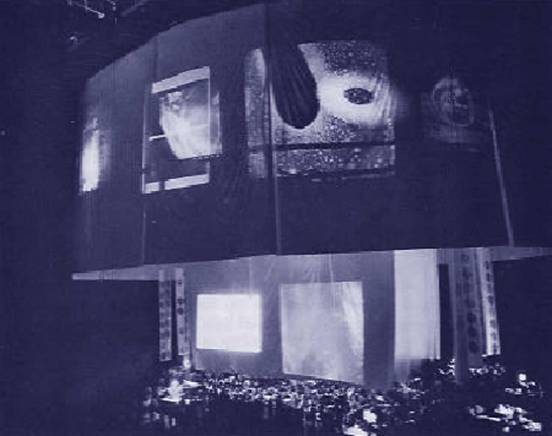

Ray and Charles Eames: still from Information Machine multi-screen presentation in the IBM Egg pavilion at 1964 World’s Fair. This kind of dynamic, multi-screen audio-visual display, piloted by the Eames at the Moscow World’s Fair in 1959 was the kind of innovation to be expected from this adventurous design duo (Charles the architect/designer, Ray the film-maker/designer), and this medium (multi-screen audio-visuals) was to be more thoroughly explored by a range of film-makers and designers a few years later at the Montreal Expo67.

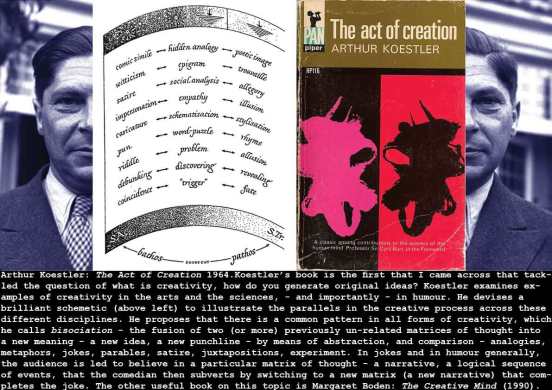

Arthur Koestler: The Act of Creation 1964

There is of course a third book on this subject that I found really useful – and whereas Margaret Boden’s insights came from her work in artificial intelligence and computer-science, Mihaly Csikzentmihalyi comes from a psychological point of view in his: Creativity – Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention (1997). Mihaly applies his theory of Flow to the issues of creativity, invention and discovery. Flow is Mihaly’s descriptor for that delightful mental state we all enjoy when we are thoroughly immersed in an activity of our choosing – when we are on form, totally mentally, physically and emotionally immersed in a creative act. All three books – spanning some 30 years or more – are essential reading for those of us engaged in creative processes or trying to encourage creativity through teaching.

Michael Moorcock (ed) New Worlds Speculative Fiction (from 1964-1970)

In my teens – looking for good reading outside – or as well as – the standard literary canon, I had discovered the joys of science fiction, and read most of classics – Isaac Asimov’s Foundation and Empire trilogy, Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, Harry Harrison’s Stainless Steel Rat, Vonnegut’s Sirens of Titan, (etc), so discovering the state-of-the-art scifi – that is sci-fi + avant garde adventurous writing – in the pages of New Worlds was just perfect.

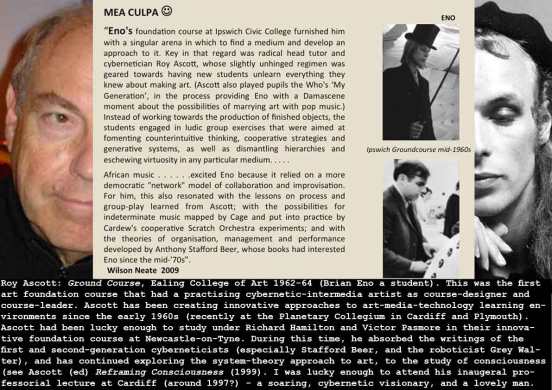

Roy Ascott: Ground Course, Ealing College of Art 1962-64 (Brian Eno a student)

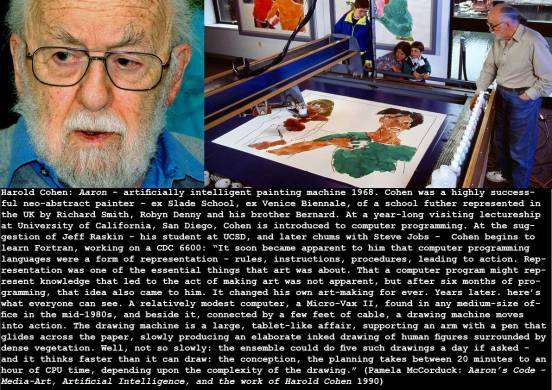

My esteemed colleague Richard Oliver was a student at Ealing on Ascott’s Ground Course (which is recommendation enough for me), and Ascott’s innovative work in restructuring art-school education by injecting his notions of collaboration, mutual learning, feedback, and other ideas current in the wave of British cybernetic thinking at this time (the work of Pask, Stafford Beer, Grey Walter, Harold Cohen and others) – added another important range of ingredients to the evolving art-education model that resulted in a new degree – the Diploma in Art and Design – launched in 1963 – my first year at Art School.

Stanley Kubrick + Pablo Ferro: Trailer for Dr Strangelove or How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

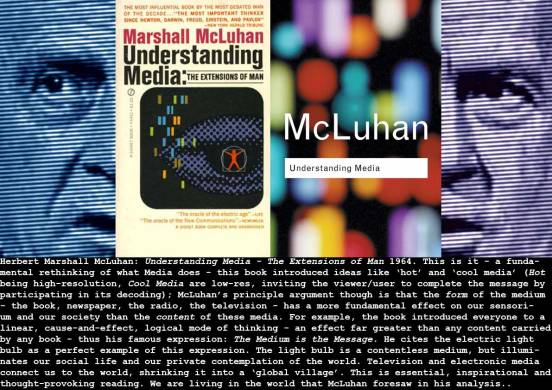

Herbert Marshall McLuhan: Understanding Media – The Extensions of Man 1964

“After three thousand years of explosion, by means of fragmentary and mechanical technologies, the Western world is imploding. During the mechanical ages we had extended our bodies in space. Today, after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned. Rapidly we approach the final phase of the extensions of man – the technological simulation of consciousness, where the creative process of knowing will be collectively and corporately extended to the whole of human society, much as we have already extended our senses and our nerves by the various media. Whether the extension of consciousness, so long sought by advertisers for specific products, will be a ‘good thing’ is a question that admits of a wide solution. There is little possibility of answering questions about the extensions of man without considering all of them together. Any extension, whether of skin, hand or foot, extends the whole psychic and social complex.” Marshall McLuhan from the Introduction, Understanding Media 1964 p11)

Hubert Selby Jr: Last Exit to Brooklyn 1964

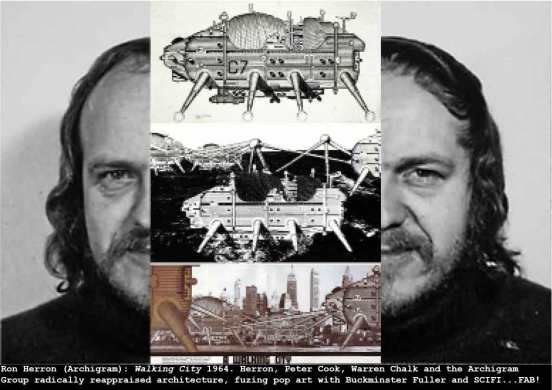

Ron Herron (Archigram): Walking City 1964

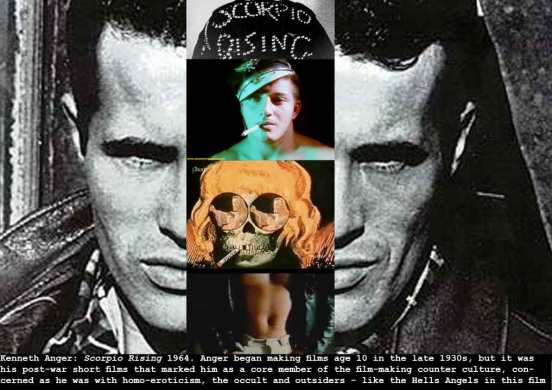

Kenneth Anger: Scorpio Rising 1964

If Tom Wolfe (Kandy Kolored Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby 1965) and Hunter S. Thompson (Hells Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, 1967) invented embedded or ‘gonzo’ journalism in 1965-66, Kenneth Anger was doing his best to create embedded documentary in the early 1960s. This is his homophiliac hymn to the motorcycle gangs that fascinated Thompson – a study in punk street cool, homoerotic posing, the body language of the social outsiders, occult magic practice, rebel icons… Scorpio Rising made the headlines at its first screening in Hollywood: “someone denounced it to the Hollywood vice squad and they raided the theater and took the print. And the case had to go to the California Supreme Court to be freed and then it became, like, a landmark case of redeeming social merit. That was the phrase that was used to justify that it wasn’t pornography. And, indeed, there’s nothing pornographic about it. Somebody had to break the ice and have that kind of case at that time to establish the freedom, because, before then, the police could seize anything they wanted to. What I was doing on the West Coast, Jack Smith was doing on the East Coast with Flaming Creatures. The two films happened at about the same time.” (Kenneth Anger)

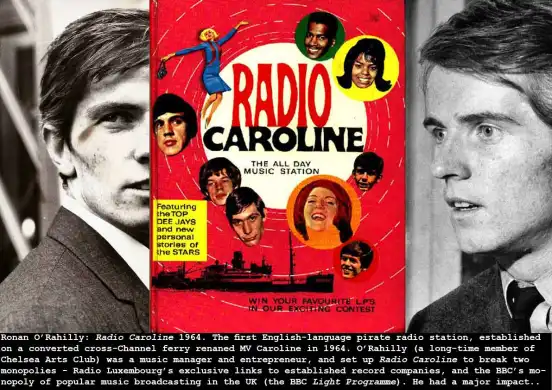

Ronan O’Rahilly: Radio Caroline 1964

Augusto de Campos: Eye for Eye (1964)

Ken Knowlton + Stan Vanderbeek: Poemfield (1964)

William Seward Burroughs: Nova Express 1964

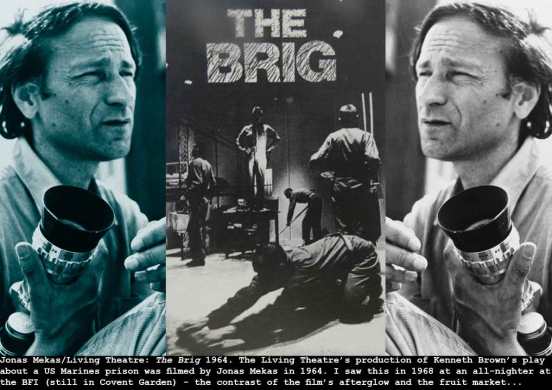

Jonas Mekas/Living Theatre: The Brig 1964

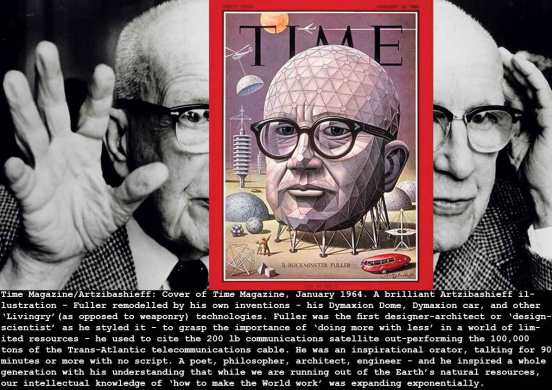

Time Magazine/Artzibashieff: Cover of Time Magazine, January 1964

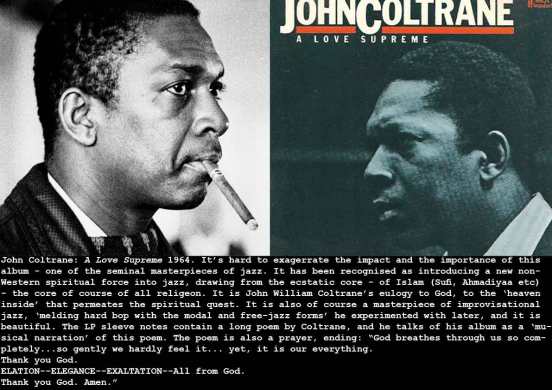

John Coltrane: A Love Supreme 1964

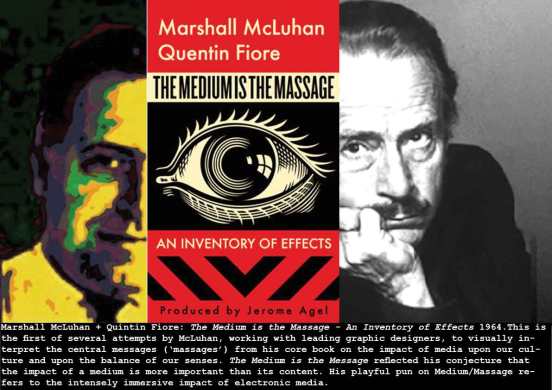

Marshall McLuhan + Quintin Fiore: The Medium is the Massage – An Inventory of Effects 1964

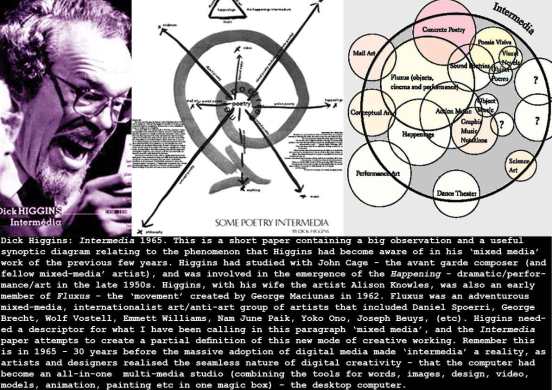

Dick Higgins: Intermedia 1965

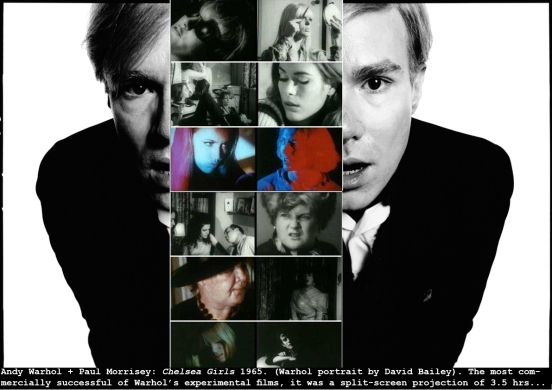

Andy Warhol + Paul Morrisey: Chelsea Girls 1965

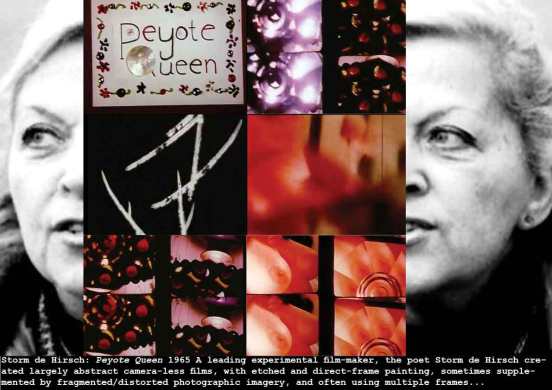

Storm de Hirsch: Peyote Queen 1965

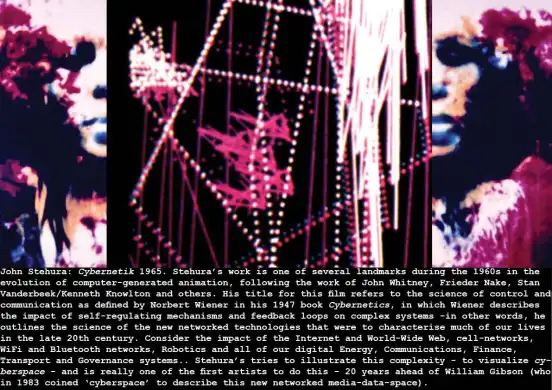

John Stehura: Cybernetik 1965

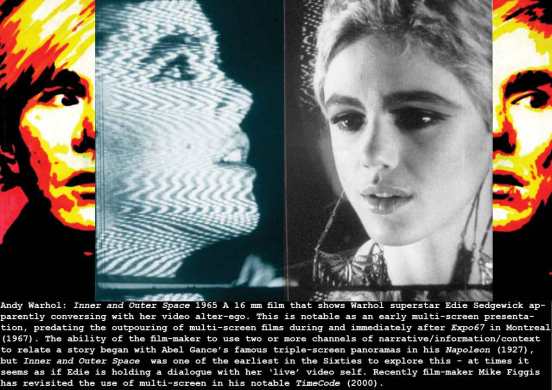

Andy Warhol: Inner and Outer Space 1965

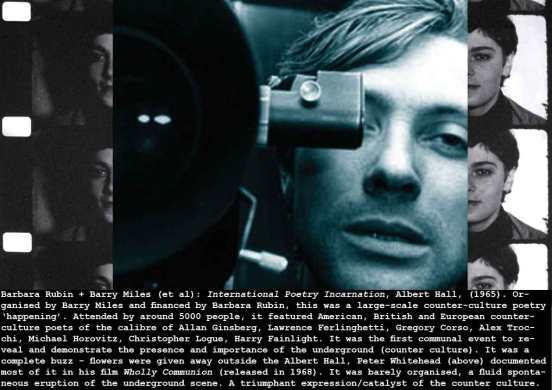

Barbara Rubin + Barry Miles (et al): International Poetry Incarnation, Albert Hall, (1965)

It’s hard to exaggerate the feeling we had in the mid-Sixties (though really gradually from the late 1950s) of the slow emergence and increasing coherence of a post-War counter culture (it was still called the ‘underground’ then). It was at the Royal Albert Hall in 1965 when the scale of this emergence became visible and tangible. Suddenly we knew we weren’t alone – here were the people like us! This zeitgeist event, organised by Barry Miles, funded by Barbara Rubin, and supported by a galaxy of important alternative voices in the underground ‘reincarnation’ of poetry – apart from Adrian Mitchell’s brilliant To Whom it May Concern (film above), it was Harry Fainlight shooting his poem, wrapped around an arrow, into the audience. And it was a beautiful American woman (was this Barbara Rubin herself?), whirling her wrist-strapped Bolex 16mm camera around her body as she stood in the whirling, swirling centre of the Hall, with Ginsberg intoning his shamanic rituals, with people giving visitors flowers on the august steps of the Albert Hall, under the approving gaze of Albert (from the Albert Memorial across Kensington Gore). Here we were! Something was happening! It was a revelation of the New! It was a huge relief, proof that we had an alternative. We loved it!

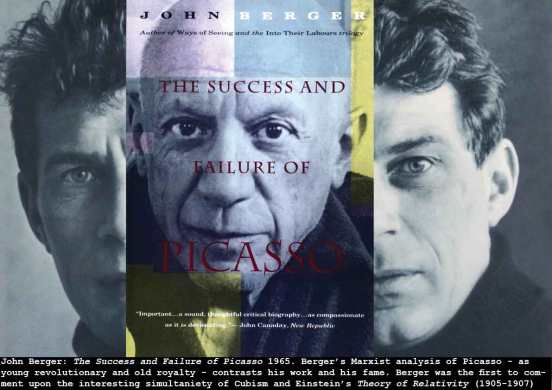

John Berger: The Success and Failure of Picasso 1965

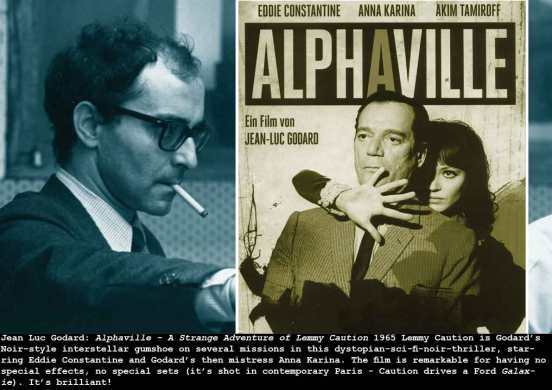

Jean Luc Godard: Alphaville – A Strange Adventure of Lemmy Caution 1965

Yoko Ono: Cut Piece 1965

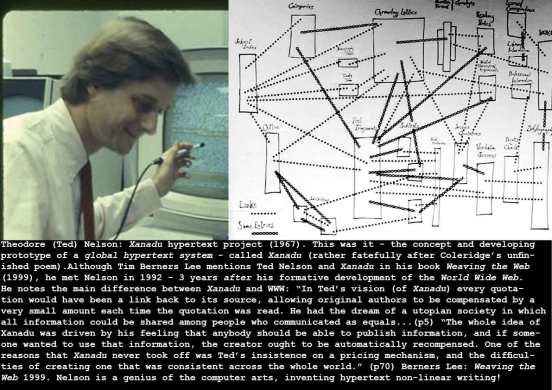

Ted Nelson: Hypertext 1965

A digital extension of the ideas embodied in Vannevar Bush: As We May Think (1946), Nelson’s ingenious breakthrough was to conceive of how dynamically and electronically linked text might be. He worked with Andries van Dam of Brown University to build a prototype hypertext editing system in 1967, and thus prepared the way for the global World Wide Web of Tim Berners Lee in the 1990s. This is the common basis for our textual and multimedia communications of the 21st century.

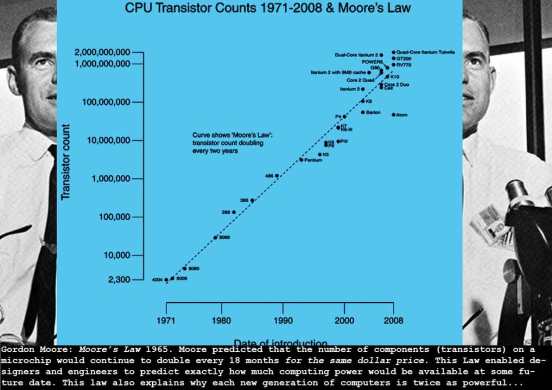

Gordon Moore: Moore’s Law 1965

Tom Wolfe: The Kandy Kolored Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby (1965)

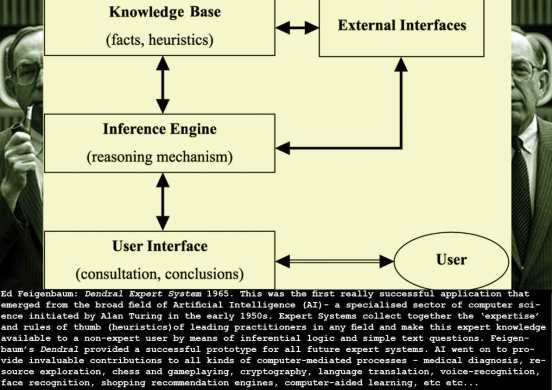

Ed Feigenbaum: Dendral Expert System 1965

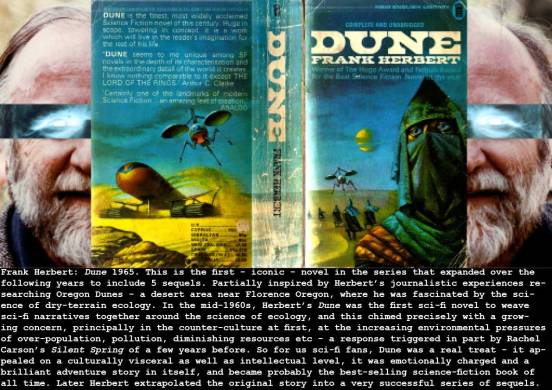

Frank Herbert: Dune 1965

It might be argued that Dune both catalysed and symbolised the wave of concern about the environment, about diminishing natural resources, about ‘ecology’ in general – that grew to become a core element in the counter-culture that emerged in the West from the mid 1950s on. His knowledge of ecology and his integration of this knowledge in his exciting fable of a galactic future in which interstellar space travel is the monopoly of an elite who rely on a drug only found on the planet Dune to give them the prescience and foresight to guide their space-ships through hyperspace – seemed to place ‘ecology’ in the centre of his story. The book’s theme – a war between competing factions to control this rare drug, seemed to be a metaphor for the growing environmental concerns of the baby-boomer generation. And this was several years before Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, before Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace…

Peter Watkins: The War Game 1965

Ivan Sutherland: Head-mounted Display 1965

US Government (Lyndon Johnson): ICBM ‘Survivable’ Defence System 1965

Jérôme Savary: Compagne Jérôme Savary/Grand Magic Circus 1965

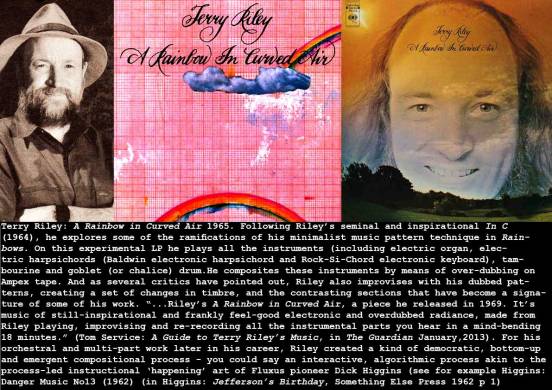

Terry Riley: A Rainbow in Curved Air 1965

For me, the best introduction to Riley’s work (and to the other key minimalists) is the series Tones, Drones And Arpeggios: The Magic Of Minimalism “Musician Charles Hazlewood explores the four great American minimalist composers who rebooted classical music in the 20th century. Beginning with the pioneering experiments of Californians La Monte Young and Terry Riley, this two-parter culminates in Philip Glass and Steve Reich’s mesmerizing work in New York.” (BBC description). To gauge the quality and diversity of Riley’s music see the following clip:

Terry Riley: A Rainbow in Curved Air 1965

Note by Serge2K on Youtube: “After several graph compositions and early pattern pieces with jazz ensembles in the late ’50s and early ’60s (see “Concert for Two Pianists and Tape Recorders” and “Ear Piece” in La Monte Young’s book An Anthology), Riley invented a whole new music which has since gone under many names (minimal music — a category often applied to sustained pieces as well — pattern music, phase music, etc.) which is set forth in its purest form in the famous “In C” (1964) (for saxophone and ensemble, CBS MK 7178). “Rainbow in Curved Air” demonstrates the straightforward pattern technique but also has Riley improvising with the patterns, making gorgeous timbre changes on the synthesizers and organs, and presenting contrasting sections that has become the basic structuring of his works (“Candenza on the Night Plain” and other pieces). Scored for large orchestra with extra percussion and electronics, some of this work’s seven movements are: “Star Night,” “Blue Lotus,” “The Earth Below,” and “Island of the Rhumba King.”

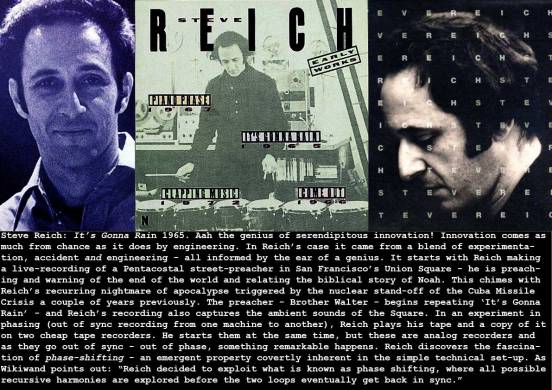

Steve Reich: It’s Gonna Rain 1965

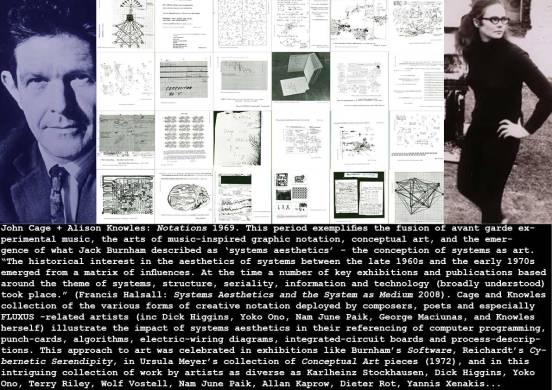

Charles Hazlewood explores the ‘last great classical-music revolution’ – the invention and development of minimalism from the late 1950s to the mid 1970s. In this 2018 BBC documentary he talks to La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Philip Glass, Steve Reich and other musicians and critics whose work and ideas have been influenced or inspired by minimalism. As I hinted above, much of the impetus and inspiration for this radical re-conceptualising of ‘serious music’ came from the radical rethinking of John Cage, and as Cage was fascinated by the potential of performance and exploring different media, so too were the minimalists exploring ideas shared by the Fluxus and Happenings artists of this period (Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Alan Kaprow etc). And see the collection of graphic notations collated by John Cage and Alison Knowles (Notations, 1969). Essentially, these composers and musicians – and the Happening artists themselves, were beginning to explore an algorithmic approach to art, an approach that revealed emergent properties (such as phase-shifting) in the crude analogue recording technologies of the period.

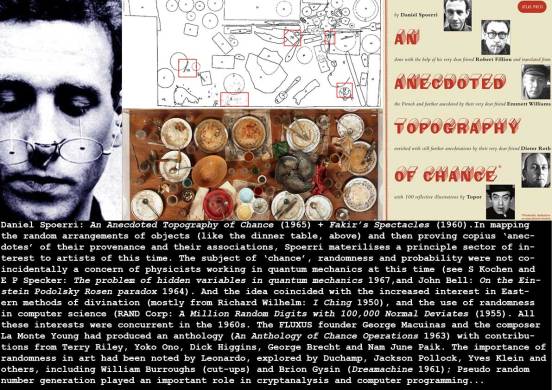

Daniel Spoerri: An Anecdoted Topography of Chance (1965) + Fakir’s Spectacles (1960)

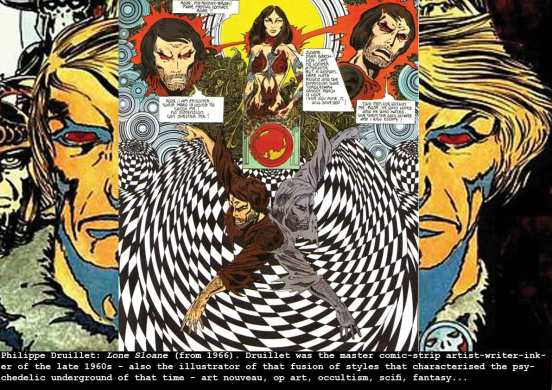

Philippe Druillet: Lone Sloane (from 1966)

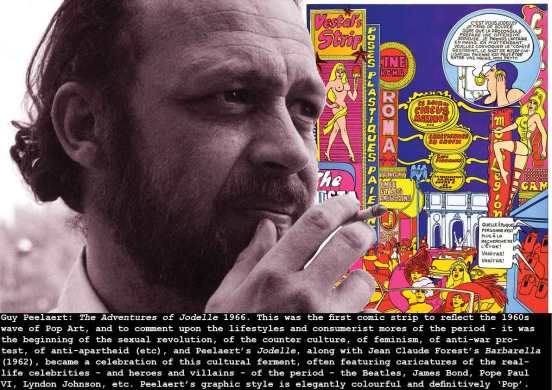

I discovered Druillet’s fabulous bande dessinee in the Shakespeare and Co Bookshop on a visit to Paris in 1969 with the writer Chris Robbins and my wife Jenny. I’d seen some American underground comics in the UK, but this was comic-strip art raised to the level of fine art – printed on coated art paper, published in hard-back, and containing Druillet’s personal mix of sci-fi, fantasy, counter-culture life-styles, hippie mores, op-art, pop-art, and Escher-like comic-strip framing. Druillet’s counter-culture hero, Lone Sloane, wanders through inter-galactic hyper-space like Godard’s Lemmy Caution (in Alphaville), Jean Claude Forest’s Barbarella (1962-1964) and Guy Peelaert’s Jodelle (1966). The French attachment to the medium of the comic-strip was a revelation, yet seemed to fit with their invention of cinematography – the mysteries of the serial image explored in two coeval media…

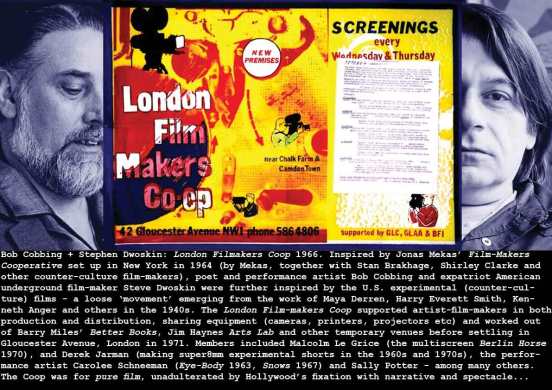

Bob Cobbing + Stephen Dwoskin: London FilmMakers Coop 1966

During this period I was at Art College, where the London Film-makers Coop was just an inspirational rumour, with Malcolm Le Grice’s work shown at the Film Society. The following year I was at Hornsey Light/Sound Workshop, for a post-graduate year, exploring multi-screen narrative films. In 1968, the Light/Sound Workshop, run by Clive Latymer, and working with Peter Cook and Dennis Crompton of Archigram, exhibited a swathe of multi-screen films/installations at Oxford MOMA. Much later, in the late 1990s I was to catch up somewhat with LFC. In 1997, the London Film-makers Coop, moved together with London Video Arts to the Lux Centre in Hoxton Square in London’s Shoreditch. At this time I was working with Malcolm Garrett’s AMX Digital, and we were based in Curtain Road, just around the corner. Shoreditch and the local ‘Shoreditcherati’, became the latest creative hub, artists, designers and developers moving into the cheaper Victorian property just east of the City. So new bars and restaurants popped up, one of the most famous and possibly the coolest was Seng Watson’s Shoreditch Electricity Showroom – just round the corner from Lux (apparently Shoreditch was one of the earliest parts of London to have electricity and electric street lighting installed). Lux was created by the curatorial genius Gregor Muir (author of Lucky Kunst (2009) – a memoir of this period in Shoreditch – and since 2011 at the Tate Modern and the ICA). It was an exciting place to be. And a few years later starting a fellowship at London College of Communications, (part of University of the Arts, London) and Alan Sekers introduced me to Malcolm Le Grice, and we had a buzzy lunchtime together.

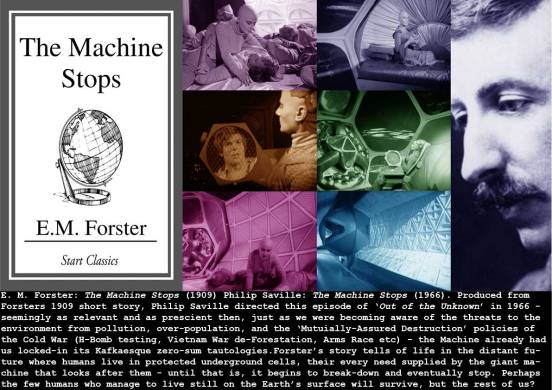

E.M. Forster: The Machine Stops (1909) + Philip Saville: The Machine Stops (1966)

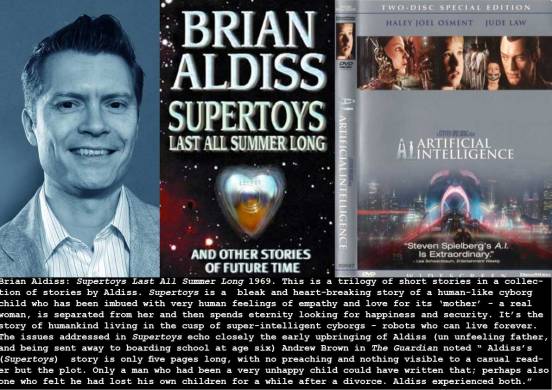

I watched this programme on TV (in my dreams – on a Sony 7″ portable – the ‘in’ TV in those days) and was electrified – here was a vision of the future from Forster’s 1909 short story – the only sci-fi he wrote, brilliantly fit for our time – a vision of people living underground (the word had other connotations then) and connected together only by machines – viewing machines that connected everyone by screen-based (video-phone style) media. This was a prescient, dystopian vision of our 21st century modern world! But Forster was taking another slant from the H.G. Well’s vision of the future (his 1895 novel The Time Machine), and Forster has the machine stop and doom the humans unable to reject or escape from their cosseted machine-reliant environment. The TV programme starred Michael Gothard and Yvonne Mitchell as the main protagonists, with direction by Peter Saville and scenographics by Norman James, and it immediately went into my mental list of important zeitgeist movies. In the 1960s the sci-fi genre began to transcend its pulp-fiction roots. Under Michael Moorcock’s guidance science fiction had become ‘speculative fiction’ and embraced a much wider range of narratives, literary forms and exciting experimentation, and some British authors were in the avant garde of this new wave – John Brunner, J.G. Ballard, Brian Aldiss – and the influence of the expatriate American William Burroughs – and of course Moorcock himself. The best organ for this new thinking was New Worlds – a pulp magazine originating in 1946, but under the editorial lead of Moorcock, and with a new magazine-style format since 1964. New Worlds impacted strongly on the emerging counter-culture, and borrowed from techno-optimist visionaries like Richard Buckminster Fuller, and Marshall McLuhan. It featured contemporary artists like Eduardo Paolozzi some great cartoonist-illustrators like the brilliant Mal Dean. The 1966 television remediation of The Machine Stops fitted exactly in this new wave of avant garde sci-fi. And it fitted perfectly with the ideas for the Galactic Network (the nascent Internet) formulated and published by Joseph Licklider in 1962 at DARPA. Fact and Fiction were galloping neck and neck into the future.

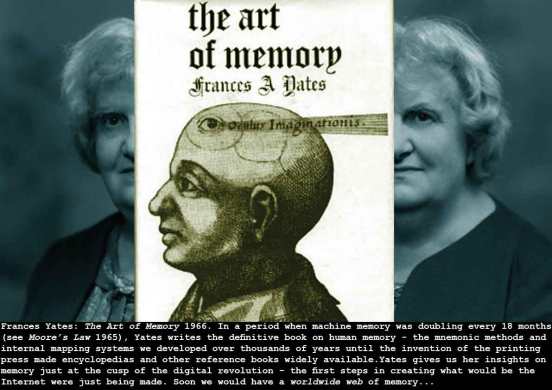

Frances Yates: The Art of Memory 1966

This became an important book for me when I discovered it in the 1980s. As part of the research for our Hypercard magazine High Bandwidth Panning (1987), the discovery of pre-Print memory techniques – memory theatres, memory palaces, rhyming mnemonics, diagrams of memory – all these methods of training and honing human memory provided a fund of metaphors for those of us interested in hypermedia, and what Vannevar Bush called ‘associative trails’ of information.

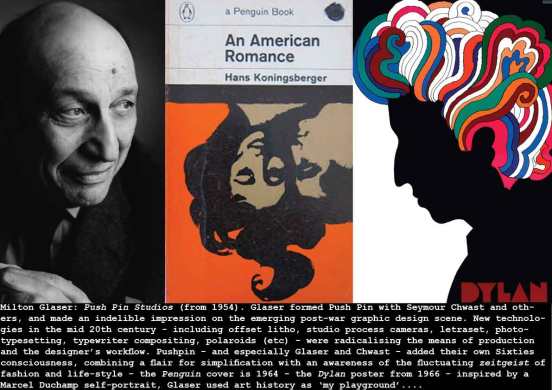

Milton Glaser: Push Pin Studios (from 1954)

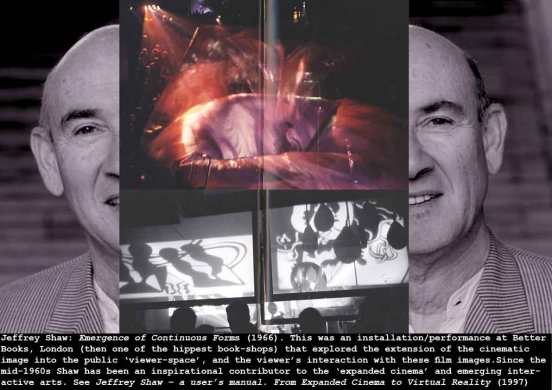

Jeffrey Shaw: Emergence of Continuous Forms (1966)

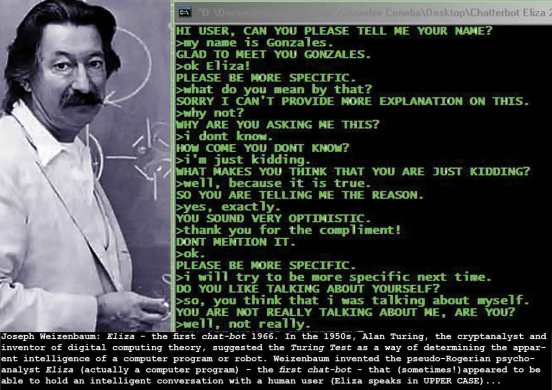

Joseph Weizenbaum: Eliza – the first chat-bot 1966

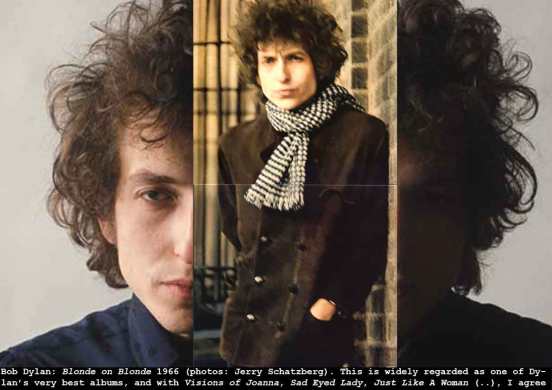

Bob Dylan: Blonde on Blonde 1966

Barry Miles + Tom McGrath: International Times (IT) 1966

Guy Peelaert: The Adventures of Jodelle 1966

The fashions, the insouciance and newly won sexual freedom (burn your bras!) of the 1960s was captured in Peelaert’s elegant graphic style – here in the hot colours that were de rigour in the mid-1960s. Guy Peelaert honed his graphic-narrative skills on Jodelle, and produced his masterpiece Rock Dreams in 1974.

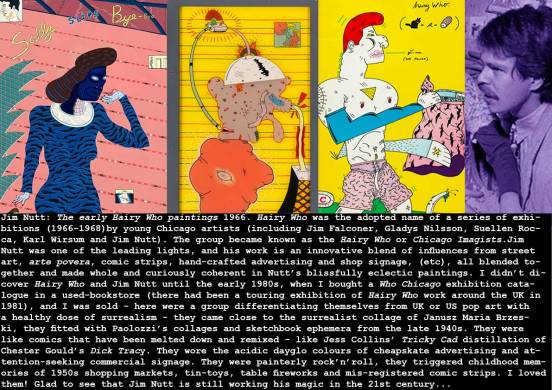

Jim Nutt: The early Hairy Who paintings 1966

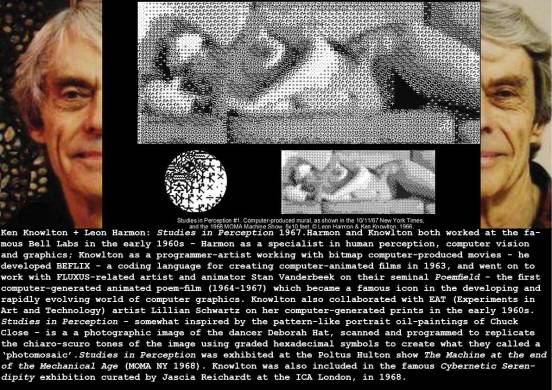

Ken Knowlton + Leon Harmon: Studies in Perception 1967

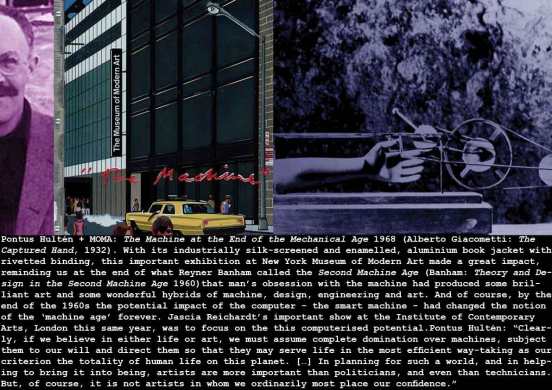

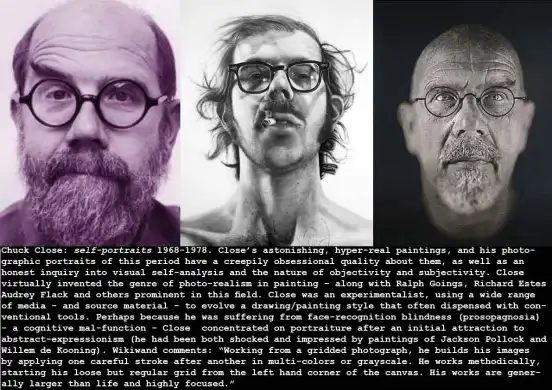

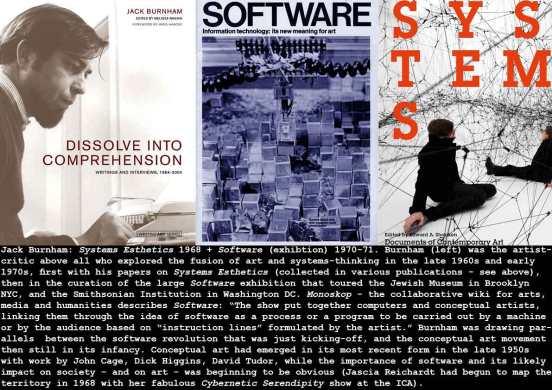

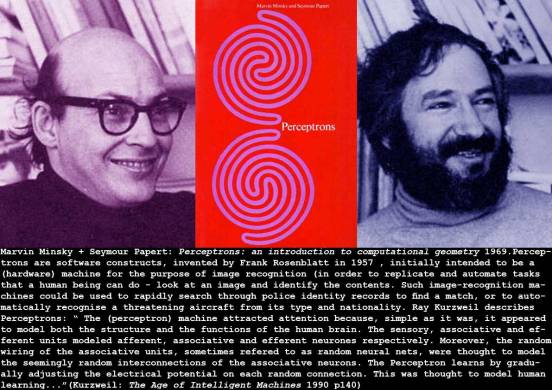

The art of computer graphics and computer-mediated art was just being explored in the 1960s, with key works by Ken Knowlton, Charles Csuri, Ivan Sutherland, Ted Nelson and others working the field, which embraced a wide range of application-areas of study, ranging from human-computer-interface design, videogames, simulation, systems dynamics, 3d modelling, animation, ergonomics design, engineering computer-aided design (etc). Within a couple of years, this developing area was mapped with important overview shows at MOMA and the ICA, and Jack Burnham’s Software exhibition at the Jewish Museum NYC (1968), and in 1970 the critic Gene Youngblood compiled a survey of new media art in his book Expanded Cinema, which included a section on computer-generated art, and included Knowlton’s work. Developments in computer hardware (especially the IBM 2250 Graphics Terminal, and the Lincoln Labs TX2 (for which Ivan Sutherland wrote his Sketchpad software), though these were mainframe computers – it was lucky artist-coder partnerships – like Knowlton and Vanderbeek – that began to edge computer graphics away from its origin in engineering computer-aided design (pioneered by Boeing Aircraft in USA and Renault Automobiles in France).

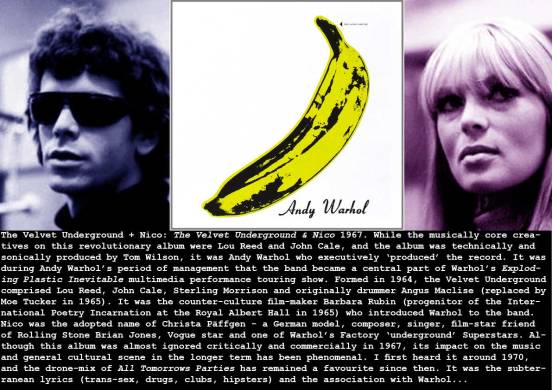

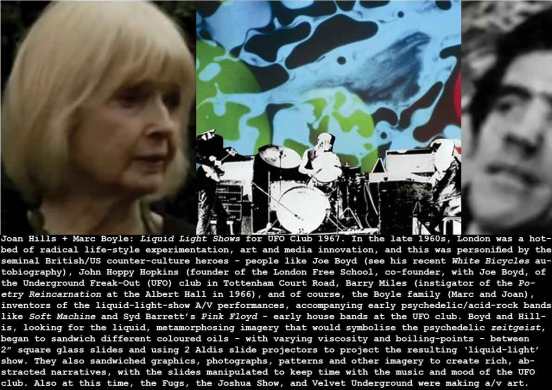

The Velvet Underground + Nico: The Velvet Underground & Nico 1967

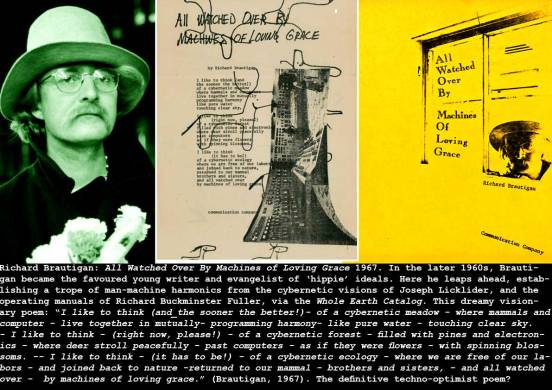

I was lucky enough to meet John Cale and Nico (at separate times) in the 1980s. Nico came to my wedding to Debbie Bury at Stephen Bartley’s Church Street Gallery. She was brought along by Ronnie Terrill, and carried the glamour and sophistication of her youth (she was in her sixties) – the superstar of the counter culture, with the kind of impeccable underground pedigree that culminated in her Velvet Underground days. Meeting in the garden of the Chelsea Arts Club, Cale was the hyper-talented musician and consummate hipster still. Intrinsic with the content and style of the zeitgeist music and lyrics, Andy Warhol’s sleeve design was at one with the album – a plastic banana that invited you to peel it back to reveal the hidden image beneath – no less that a flesh-coloured banana (!). This has the ingenuity and flair of Warhol’s other graphic work – the early, stylish illustrated jazz sleeves – and the infamous Rolling Stones Sticky Fingers sleeve, and seems to eschew graphic-design fashion in the same way that Richard Hamilton designed the Beatles White Album. Nico had already appeared on a Bill Evans sleeve:

Nico featured on Bill Evans cool Moonbeams LP, 1962

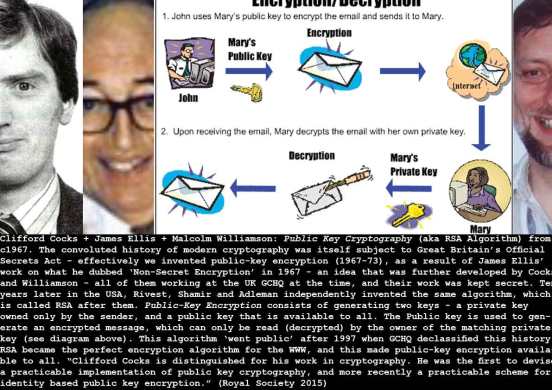

Clifford Cocks + James Ellis + Malcolm Williamson: Public Key Cryptography (aka RSA Algorithm) from c1967

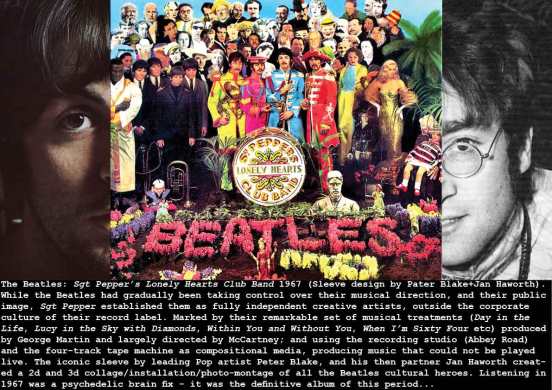

The Beatles: Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band 1967

This double-album came out in that delightful period when you carried significant LPs about with you as a kind of badge of membership of the cognoscenti – just as having long hair on men, belled trousers, full-length Afghan sheepskins, skinny-rib t-shorts and paisley jackets..(etc), these things were part of the I.D. parade of unfolding Sixties culture. But for art students and designers the Sgt Pepper album had an even greater significance – the cover was designed by Peter Blake – one of the great British Pop-Art pioneers (along with Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton), and WHAT’S MORE it contained references to many of the cult heroes of recent times – and these included a leading icon of the Beat movement (William Seward Burroughs); Mystics (Alastair Crowley, Mahavatar Babaji, Sri Yuckteswar, Lahiri Mahasaya); an Electronic-Music composer (Karlheinz Stockhausen); several Film Stars (Mae West, W.C. Fields, Tom Mix, Huntz Hall, Tyrone Power, Tony Curtis, Marilyn Monroe, Marlon Brando, Shirley Temple, Fred Astaire, Johnny Weissmuller, Marlene Deitrich), avant garde and music-hall comedians: (Lenny Bruce, Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy, W.C. Fields, Issy Bonn, Tommy Handley), a footballer (Albert Stubbins); communist-theorist (Marx),; scientists (Carl Jung, Albert Einstein, Dr Livingstone); writers (George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, Stephen Crane, Lewis Carroll, Oscar Wilde, Terry Southern, Dylan Thomas, Edgar Allen Poe, Aldus Huxley; some cool artists (Richard Lindner, Wallace Berman, Richard Merkin, Simon Rodia, Stuart Sutcliffe, Larry Bell, Aubrey Beardsley) and some rockstars – Bob Dylan, Bobbie Breen, Dion (of the Belmonts) – and a few others!

Having a pictorial code of Beatles counter-culture heroes to discuss was like a cult book – not since Bob Dylan’s first album, not since the Tom Lehrer L.P.s, since Christopher Logue’s Red Bird, or John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, or Stockhausen’s Gesang der Junglinde, since Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde double-album, had Long-Playing records been so cool.

Thanks Peter Blake and Jann Haworth, John, Paul, George and Ringo, and George Martin – and Michael Cooper who took the Edwardian uniform pictures. Inspirational!

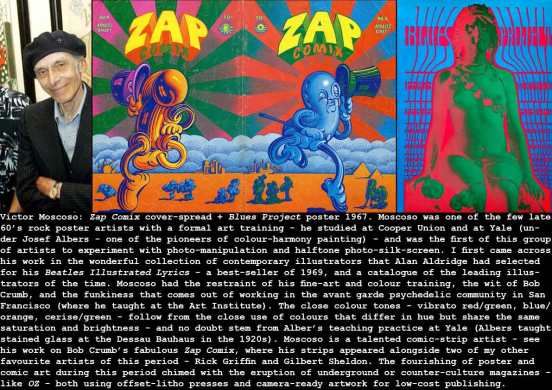

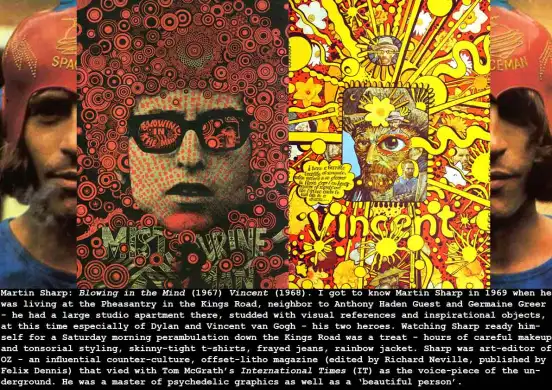

Victor Moscoso: Zap Comics cover-spread 1968 + Blues Project poster 1967

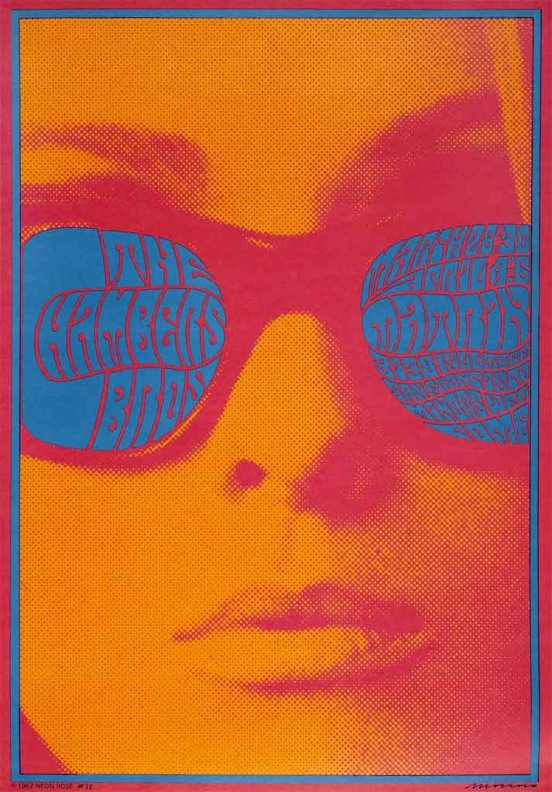

Victor Moscoso: Chambers Brothers poster 1967 – Moscoso seamlessly integrates enlarged half-tone portrait into his psychedelic poster – those vibrating colour tones!

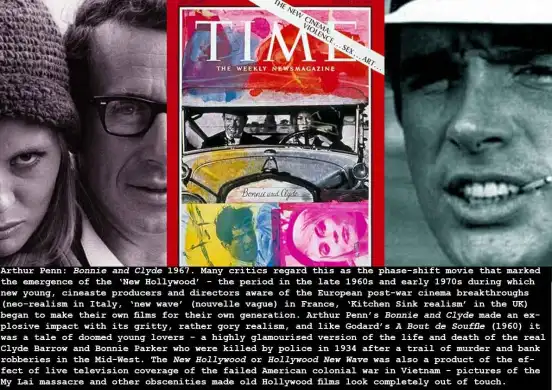

Arthur Penn: Bonnie and Clyde 1967

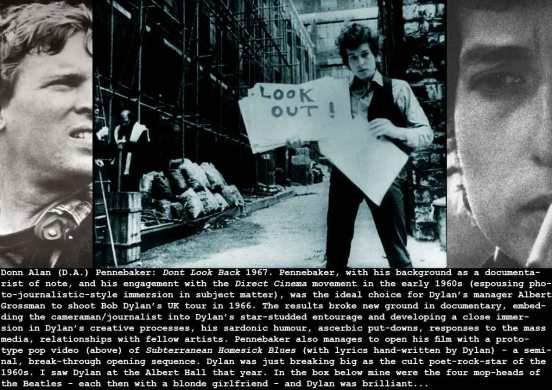

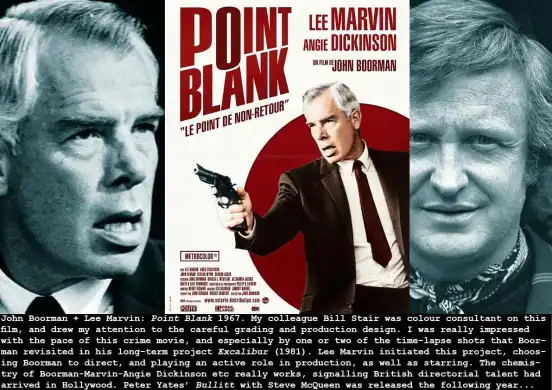

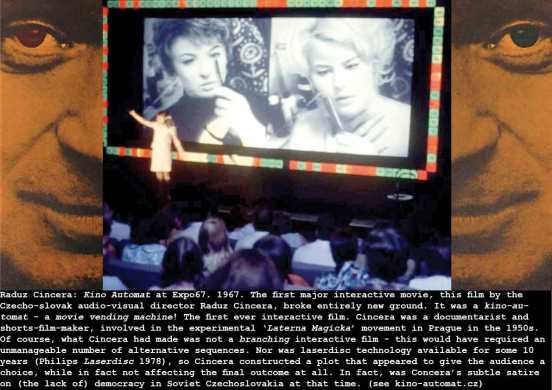

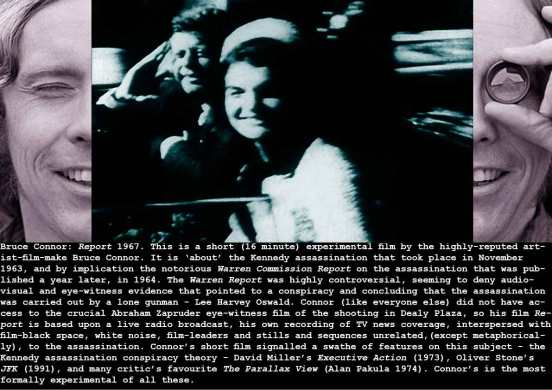

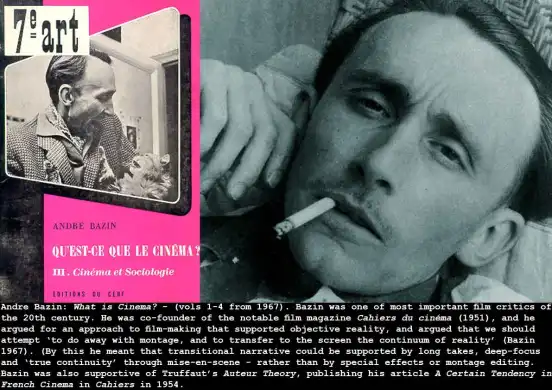

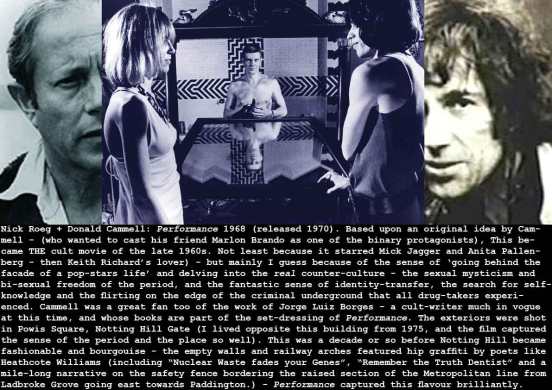

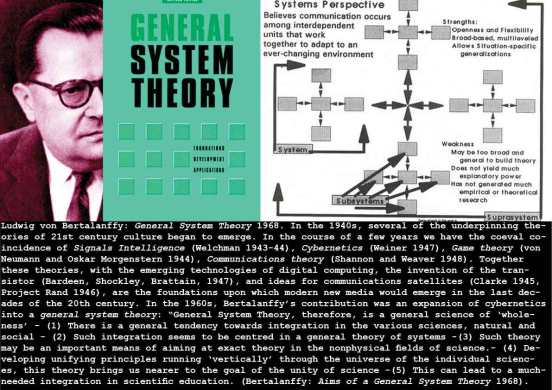

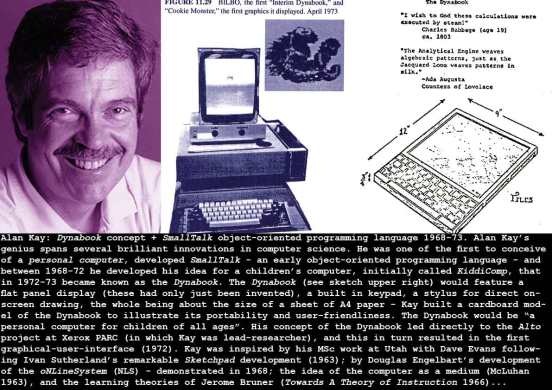

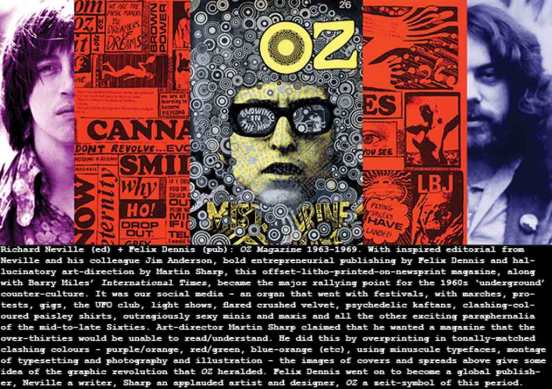

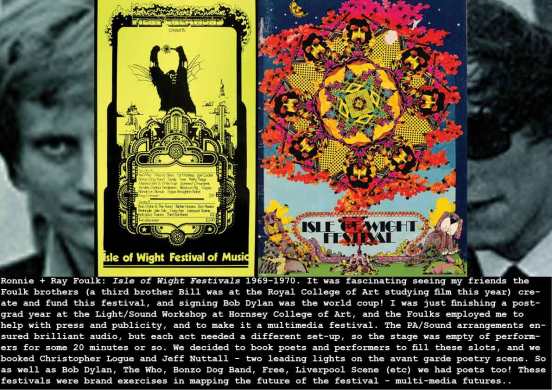

Donn Alan (D.A.) Pennebaker: Dont Look Back 1967